The Conversation that Built America

by Taylor Mata

As I stood in my kitchen making latkes this evening, I realized why I am constantly disillusioned with America. I am an American, and there are few other places in the world I would choose to live. I grew up as all of us in the American public school system did: saying the Pledge of Allegiance every morning after singing the national anthem, America the Beautiful, or that relatively new one that nobody seems to know the name of but generally prefer to the Star Spangled Banner. I learned of American history starting way back with the history of the Native American peoples and the importance of diversity, the melting pot we take for granted, or as I prefer to call it, the salad bowl. I don’t have a problem with that.

I, and more literally the farm-to-table movement, have a problem with America’s near-complete disregard for the amount of work that goes into making a salad. Salads can have as many different components as you please, and dressings can get even more inventive. Some people like sweet, light salads, and others like them heavy and filling. Still, we can all agree on two things: a salad has a base vegetable and comes in a bowl. But what base ingredient do you choose? And where did the bowl come from? These are the questions we need to be asking.

Thankfully for us, the bowl was already there. One can argue for days about how the bowl itself got there, but we all know that bowls have to be crafted somehow. It didn’t just pop up out of nowhere into a perfect bowl-shape. It was kept in pristine condition by the Native American peoples for hundreds of years before Europeans even arrived here. America, the land that constitutes it, is our bowl, and good God, have we taken the liberty in filling it. In fact, our salad bowl started by stealing a bowl to make our salad in, dumping out the vast majority of whatever contents the true owners of the bowl had in it, and shooing them away. It alone doesn’t seem like a great salad at this point, and it wasn’t.

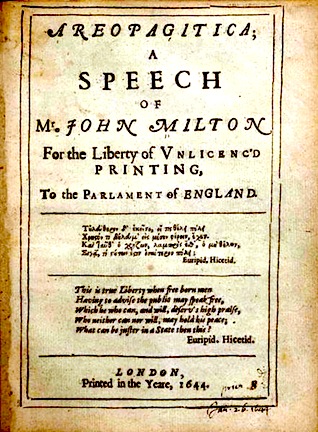

And then came the base ingredient, the greens. Greens don’t just magically appear in your stolen bowl, you know. They have to come from somewhere, planted and grown from seeds over time, and in this salad’s case, they came from words. The soil for the greens, chock-full of nutrients and moisture, came from a great literary farmer, giver of life to words, John Milton who called for a country without a monarch, a true republic in which people worked together on a quest for the best and truth. Milton campaigned for years for the cause of a more democratic England, and for a while, the possibility seemed quite real. In Aeropagitica, a speech intended for parliament, he fertilized the soil by calling for the removal of censorship. Milton’s words were rich and powerful, the kind of words that move mountains. His imagery caused the English people to think, spur them on in their own quests for progress. He fought the doubts of those who hesitated to till the soil in his reactive Eikonoklastes (or in layman’s terms, ‘breaker of the icon’), a reactionary piece written to combat the guilt-tripping and ill-founded arguments of the dethroned and executed King Charles I in Eikon Basilike (or, ‘icon of the King).

For a while, it worked. The English people were motivated for change, ready to work with this earth that Milton had laid. But some ideas are too new, and after struggling for so long, the English were not able to plant on the ground they had worked so hard to till. Milton watched in dismay as the English turned back to monarchy and his ground was barren. Yes, the soil had once been tilled by the English, but all-too-quickly was prevented from being planted in, and lay for over 100 years unused.

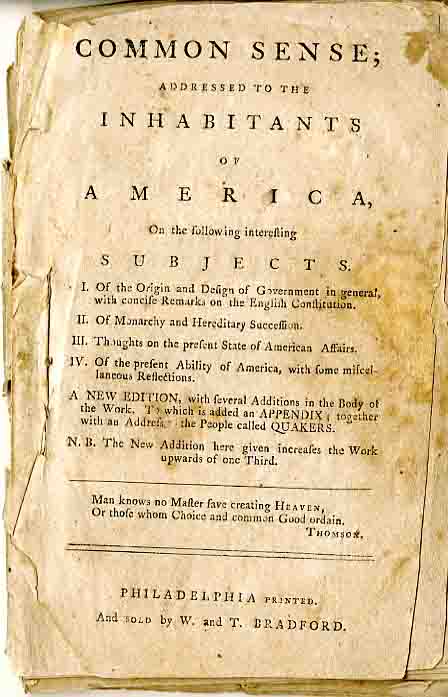

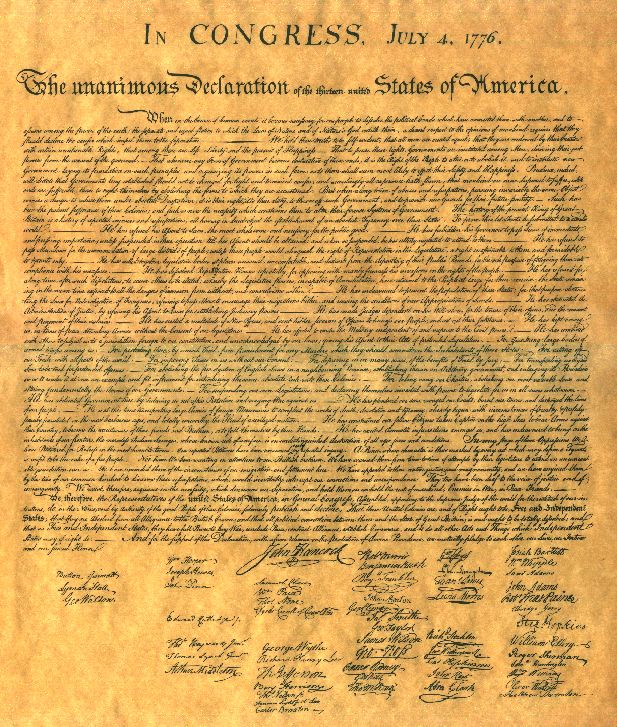

Then another literary farmer, Thomas Paine, came along and found this ground, its owner dead and gone, and started to revive it. He saw how rich the soil had been, how many nutrients were available for use, and he became the first to converse with Milton over the centuries. He tilled the ground once more, planted the seeds of revolution with his pamphlets like Common Sense and The Rights of Man, and stood proudly as people became attracted to the idea. Soon, everyone was reading these words and more and more people eyed the soil, seeing its merit. Our forefathers like Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Hancock tended these greens, evident in their addition to the conversation, The Declaration of Independence. The armies of George Washington harvested these greens, and the result was the first United States of American people, the greens, the base of our salad to be added to by those very same chefs and those who would come to seek this fresh salad bowl with so much potential.

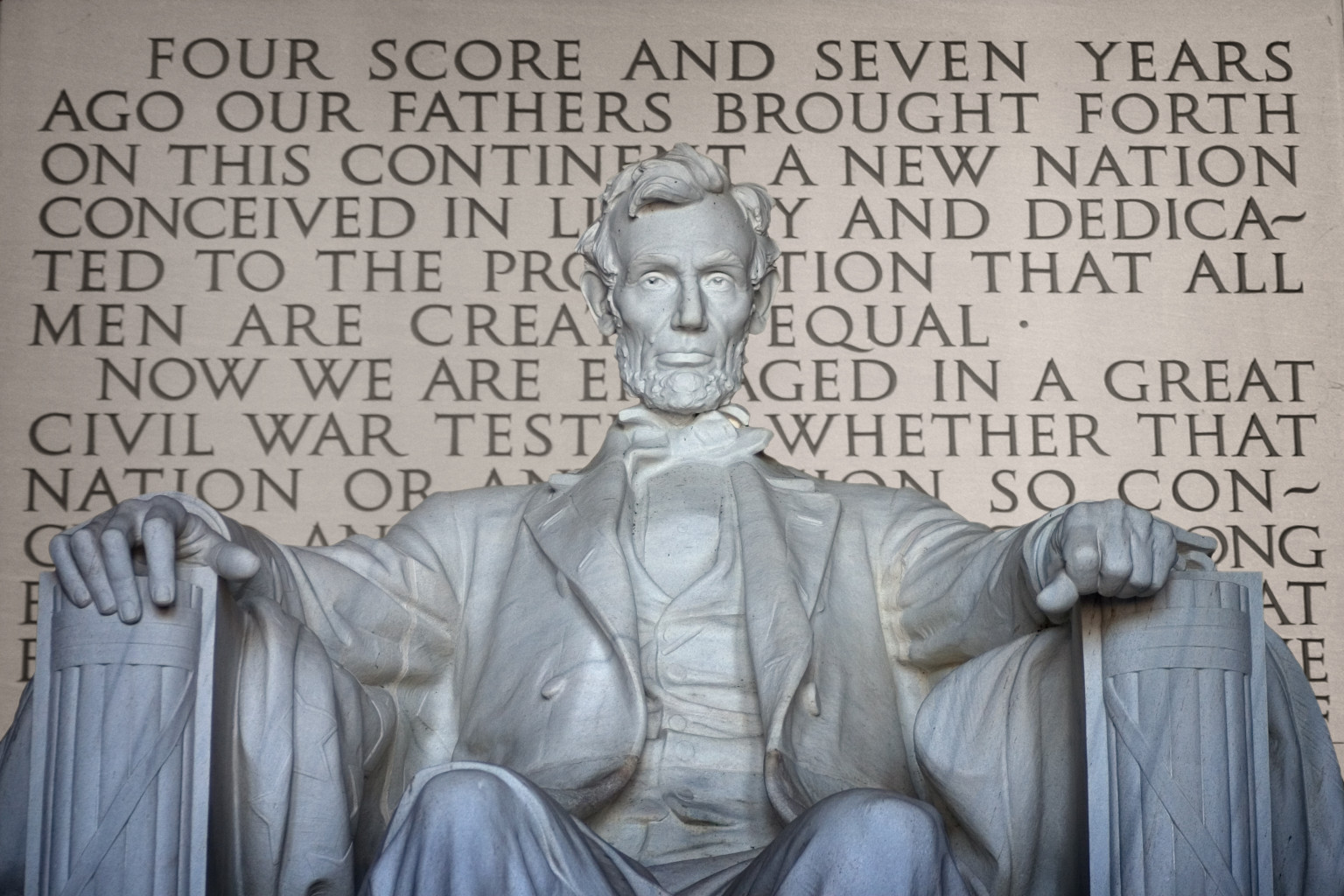

And then came the real form of collaborative cooking. For hundreds of years we, the American people, have been adding ingredients and uproarious conversations have occurred about what can go into this bowl, what spot the ingredients can have in the bowl, just how prominent those ingredients are allowed to be in the bowl, and if the flavor really fits with the kind of salad we are trying to make here. Abraham Lincoln chided the American recipe for how much trouble it had brought upon the American people in his famous Ghettysburg Address. Then one hundred years later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called for the recipe to be changed to include and represent all of America when he spoke in Washington D.C. and gave the uproariously popular speech, I Have A Dream. Even now, Americans are working hard to adjust the American recipe in their protests on inequality, not necessarily realizing that the words they preach have a lineage that reaches back further than America itself. This salad has been in production longer than we really acknowledge, and the same arguments about ingredient inclusion we are having today have happened before.

Perhaps this is why I enjoy cooking so much – probably even more than I enjoy eating which is hardly possible. Knowing where things come from is amazing. It makes everything that much more important. Chefs and psychologists alike have always said that the way to ensure a child will eat is to get them involved in the cooking conversation, to show them where their food comes from, because they will then be invested in the food. Greens are great, but when you know the where the farm is and what the farmer does and the how the workers brought those greens to rest in your bowl, isn’t that salad much more important to you?

It puzzles me that knowing this is not important to some. It confuses me that the words that created the base of our salad don’t matter to some, just the fact that there is a base and that there is a salad is enough. It doesn’t make sense to me that people believe the conversation of including ingredients in our salad has ended, was finalized ages ago, and they don’t want to continue. They just want to eat. Without the cooking conversation there would be no salad. Isn’t that important?

Looking at the foundations, I am far less disillusioned. When my salad speaks to me, and I speak back by adding the herbs I’ve grown, I come to actually respect something instead of taking it for granted. I am then proud of my salad bowl.

And so, as a person who used to want to be a chef, I’ve relegated cooking to my spare time to become an expert in the conversations that build, like the conversation that built America, the conversation that is still building America: words.

Photo sources:

- http://shakespeare.berkeley.edu/gallery2/main.php?g2_view=core.DownloadItem&g2_itemId=18219&g2_serialNumber=2

- https://www.uwrf.edu/AreaResearchCenter/ArchivesResources/images/Common-Sense-1776.jpg

- http://www.founding.com/repository/imgLib/20071018_declaration.jpg

- http://i.huffpost.com/gen/1224920/thumbs/o-GETTYSBURG-ADDRESS-facebook.jpg

- http://www.emersonkent.com/images/king_i_have_a_dream.jpg

- http://endtimeheadlines.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/B9x3lpMIIAEsVXl.png