The Literary Dialogue on Milton’s Satan

by Zach Scott

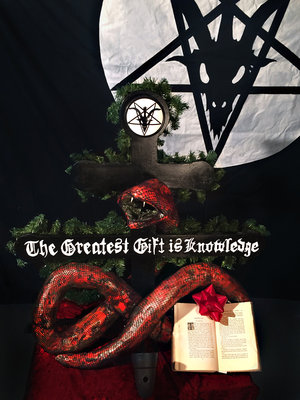

The above display—one created by the Detroit chapter of the Satanic Ministry—contains a blood-red serpent coiled around a satanic cross. Before the snake is a copy of Anatole France’s The Revolt of the Angels, and above it, surrounded by festive wreaths, is the phrase: The Greatest Gift is Knowledge.

The piece, lit by a spotlight, was displayed on the grounds of our state capitol building. It sat alongside a Christian Nativity scene, and it was installed just in time for Christmas.

Jex Blackmore, director of the Detroit chapter of the Satanic Ministry, said it was a manner of free speech:

“It’s a very important time to remind legislators and to provide and empower people who have beliefs that aren’t mainstream, this is an opportunity to have your voice be heard”

Reverend David Bullock, however, felt otherwise:

“Christmas is being hijacked by Satan . . . I understand that there is liberty. We have religious freedom, but there are limits to how these rights are supposed to be exercised.”

Both were probably unaware, though, that they were participating in a centuries-old conversation, one that includes poets and thinkers such as John Milton, William Blake, and Edmund Burke. It is a story of literary analysis that emerged from the witch burnings of 17th century England, took root in readings of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and was continued, developed, and argued through countless literary works to this day.

***

The devil was losing power in 18th century England. It was in 1684 that the last “witch” was executed in the country, and the persecution of supposed witches was made illegal in 1736. The influence of the devil was no longer feared to such a degree, and the last remnants of “Satanism” were found in what were called “rake’s clubs”. Members of such clubs regarded Satan as a figure of unbridled hedonism; they practiced public nudity, gambling, heavy drinking, and other “blasphemous” activities. The devil, to these groups, was little more than an excuse for their indulgences, and such “satanic” organizations gained little ground in English culture.

A depiction of a rake’s club painted by William Hogarth in 1733

Where Satan found a resurgence, though, was through the arts. By the late 17th century, the once-feared devil depicted in the German story of Faustus had been reduced to a joke by English dramatists. William Mountfort produced the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, made into a Farce, in 1684, and several other parodies of the satanic character followed. In fact, the defeat of Satan was even depicted in Punch and Judy shows.

These humorous depictions may have kept Satan alive, but it was through literary analysis—through a dialogue of several authors—that the image of Satan was able to gain power again.

It was John Milton’s Paradise Lost that inspired a new conception of Satan. The work, known as the last epic poem written in English, depicts Satan as the ultimate rebel. He leads a group of angels against God himself, and, when he fails to conquer heaven, he instead conquers humanity through his manipulations as a serpent in the Garden of Eden. Following this fall, Adam and Eve are left to decide between sin and submission to the divine, and it is through their submission that they are granted mortality and eventual happiness in heaven.

Poet John Dryden was the first to assert in 1697 that Satan was intended by Milton to be the hero of the epic poem. Edmund Burke’s Enquiry, a treatise which describes the “noble picture” of Satan, began in 1757 to treat the devil with an awe and “sublimity” that would later dominate the Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This approach was summed up by James Beattie in his 1783 response to Paradise Lost wherein he described the effect of Milton’s Satan as a sort of astonishing, almost guilty pleasure.

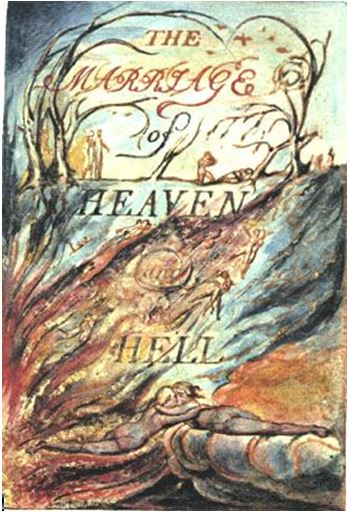

The result of this criticism and discussion, then, was a sort of smartening-up of Satan. Previous decades of debauchery and pleasure-seeking were replaced by a literary notion of the satanic sublime. One famous example of “Satanism” of this sort was found in William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell published from 1790 to 1793.

The engraving that served as the cover of Blake’s work

Included in Blake’s publication was a note on Milton’s epic poem:

Note: The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it.

Percy Shelley soon agreed with Blake. In 1821 he published a reflection on Milton:

Milton’s Devil as a moral being is as far superior to his God, as one who perseveres in some purpose which he has conceived to be excellent in spite of adversity and torture is to one who in the cold security of undoubted triumph inflicts the most horrible revenge upon his enemy, not from any mistaken notion of inducing him to repent of a perseverance in enmity, but with the alleged design of exasperating him to deserve new torments. Milton has so far violated the popular creed (if this shall be judged to be a violation) as to have alleged no superiority of moral virtue to his God over his Devil.

It is easy to see, then, that Satan had regained power in English culture. No longer a figure of black magic or superstition—no longer a figure of raucous and gratuitous sex—Satan had become a poetic symbol, one that was both sympathetic and powerful.

***

Were these literary figures correct in asserting that Milton viewed Satan as a hero? Poet Joseph Addison responded in 1712 that he did not believe Paradise Lost contained any heroes; he diminished Satan’s role in his criticism and focused instead on the characters of Adam and Eve. Readers of the epic poem will note that the majority of the work focused on these first humans, not Satan. It is Adam and Eve that are given the chance to reflect on the nature of sin and knowledge; they are dynamic, relatable figures that come to terms with their imperfections, their inevitable death, and their need to repent. Satan is merely the instigator of these realizations. It would be difficult to argue that he is the true hero of the work.

However, the image of the sublime Satan remains a part of our culture to this day. The same excitement described by Beattie is found by school children who dress as the devil for Halloween or summon demons in video games.

The Satanic Ministry draws on this excitement as well as the sort of “noble” rebellion described by Blake and others. The main tenets of modern Satanism, in fact, seem drawn directly from Milton’s portrayal of Satan:

Our position is to be self-centered, with ourselves being the most important person (the “God”) of our subjective universe, so we are sometimes said to worship ourselves . . .

Satan to us is a symbol of pride, liberty and individualism, and it serves as an external metaphorical projection of our highest personal potential. We do not believe in Satan as a being or person.

Satanism remains a controversial movement today. The aforementioned satanic display on our state’s capitol was met with a great deal of criticism, and Capitol staff spent a portion of their holiday watching the piece via security cameras to prevent vandalism.

So, if Satanism isn’t your thing, don’t blame heavy metal music or Dungeons & Dragons. The real culprit is the silent, underestimated force of literary analysis. If your child is planning to head to grad school, a worn copy of Paradise Lost in his or her backpack, it might be time you sit down and have a talk. In fact, it may already be too late.

A more complete review of Satan as a hero may be found in Kenneth Allen Bruffee’s Satan and the Sublime: The Meaning of the Romantic Hero.