A Look at Conversation Between Authors

by Brian Gebhart

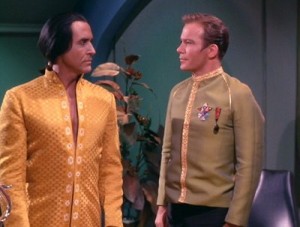

In the first season of the original series of Star Trek, Captain Kirk and the crew of the Enterprise unwittingly awaken Khan Noonien Singh, a genetically engineered warlord, from cryogenic sleep. At episode’s end, after a series of battles of both wits and fists, Kirk and co. defeat Khan. But, the famed captain opts not to re-imprison the warrior; instead, Kirk chooses to abandon Khan and his cohorts to a hostile, empty planet. But when Kirk asks his foe if he thinks he could possibly tame the planet, Khan responds with a question of his own: “Have you ever read  Milton, Captain?” It is a question to which Kirk says he understands. The oblique reference is explained later by Kirk to his crew: when Satan was cast into the pit in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, he declared it better to reign in hell than serve in heaven. For a quotation taken out of context, Milton’s is famous line, easily applicable to any scenario in which a proud man chooses a hell of his own over a heaven of another. For Star Trek, it makes for a famous scene, one that emphasizes the education and intelligence of both Kirk and Khan and amplifies their antithetical, but strangely mirroring, measures of intellect. To be sure, the writers of Star Trek may have not written that episode, “Space Seed,” with the original intent of including such a reference to the Biblical epic of Paradise Lost, but – as a subtle reference – the quotation works. It provides added depth to the characters of Kirk and Khan, and stresses that their interactions are just as much rooted in learning as they are confrontation. In extrapolation, such a scene reflects a recurring image and point of interest in the arts: the nature of quotation from one writer by another. In turn, a corresponding discussion of conversation arises – where, when, and how does one writer call another into conversation? As I recall the episode, these thoughts race through my mind – a fire certainly ignited by recent discussions with a class of mine. The question must be asked: at what point does a quotation used by one writer from another writer become conversation – that is, a dialogue or debate that attempts to understand or elaborate upon earlier contributions by writers to literature?

Milton, Captain?” It is a question to which Kirk says he understands. The oblique reference is explained later by Kirk to his crew: when Satan was cast into the pit in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, he declared it better to reign in hell than serve in heaven. For a quotation taken out of context, Milton’s is famous line, easily applicable to any scenario in which a proud man chooses a hell of his own over a heaven of another. For Star Trek, it makes for a famous scene, one that emphasizes the education and intelligence of both Kirk and Khan and amplifies their antithetical, but strangely mirroring, measures of intellect. To be sure, the writers of Star Trek may have not written that episode, “Space Seed,” with the original intent of including such a reference to the Biblical epic of Paradise Lost, but – as a subtle reference – the quotation works. It provides added depth to the characters of Kirk and Khan, and stresses that their interactions are just as much rooted in learning as they are confrontation. In extrapolation, such a scene reflects a recurring image and point of interest in the arts: the nature of quotation from one writer by another. In turn, a corresponding discussion of conversation arises – where, when, and how does one writer call another into conversation? As I recall the episode, these thoughts race through my mind – a fire certainly ignited by recent discussions with a class of mine. The question must be asked: at what point does a quotation used by one writer from another writer become conversation – that is, a dialogue or debate that attempts to understand or elaborate upon earlier contributions by writers to literature?

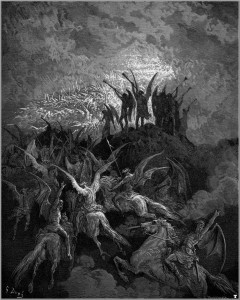

Such an idea is prevalent throughout Milton’s own work, and was a continued point of discussion in the class, “Milton and Spenser: Radicals Making a Tradition,” this past semester at the University of Michigan-Flint. As framed by Dr. Mary Jo Kietzman, our class discussions often swayed to the similarities between the two writers, and how – specifically – Milton seemed to be drawing upon the writings of Spenser. Our own conversations often led me to think about the nature of conversation among writers and artists – when, where, and why does one author comment upon another? For instance, when Milton introduces his audience to his cavalcade of demons in Pandemonium, one of his fallen, Mammon, appears to be drawn from the same well as Spenser’s own Mammon in The Faerie Queene. Spenser’s Mammon and knight Guyon’s descent into the underworld very much seem an influence in Milton’s description of hell, and appear to reinforce the idea of greed and materialism blossoming into personal, private hells. To go one step further, Mammon’s obsession with wealth and industrial growth provide contrast to the real focus of the first half of Paradise Lost: Satan, that figure who vacates servitude in heaven for a premier throne in hell – losing himself in the process.

Such an idea is prevalent throughout Milton’s own work, and was a continued point of discussion in the class, “Milton and Spenser: Radicals Making a Tradition,” this past semester at the University of Michigan-Flint. As framed by Dr. Mary Jo Kietzman, our class discussions often swayed to the similarities between the two writers, and how – specifically – Milton seemed to be drawing upon the writings of Spenser. Our own conversations often led me to think about the nature of conversation among writers and artists – when, where, and why does one author comment upon another? For instance, when Milton introduces his audience to his cavalcade of demons in Pandemonium, one of his fallen, Mammon, appears to be drawn from the same well as Spenser’s own Mammon in The Faerie Queene. Spenser’s Mammon and knight Guyon’s descent into the underworld very much seem an influence in Milton’s description of hell, and appear to reinforce the idea of greed and materialism blossoming into personal, private hells. To go one step further, Mammon’s obsession with wealth and industrial growth provide contrast to the real focus of the first half of Paradise Lost: Satan, that figure who vacates servitude in heaven for a premier throne in hell – losing himself in the process.

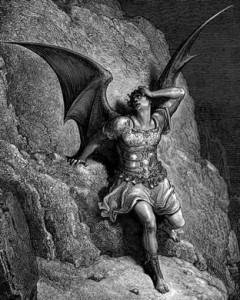

Indeed, that same concept of conversing could be applied to the entire work of Paradise Lost: that it is Milton’s attempt to converse with the author of Genesis, to elaborate and expand upon the themes he believes are already present in the Bible. As Milton says himself in the introduction to his epic, he aims to “justifie the wayes of God to men.” But what of other works that try something similar? Milton is surely not the only writer to attempt conversation with his predecessors. A similar framework of inspiration and influence is visible in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound – which was Shelley’s attempt at elaborating upon the themes he believed most important in Aeschylus’ plays of the Titan. Specifically, Shelley emphasized the rebellion of the Titan of fire against the king of gods and “Oppressor of Mankind,” Jupiter. But Shelley, like Milton, was not interested in merely copying and pasting his inspiration. As Shelley says himself in his Preface, the “moral interest of the fable, which is so powerfully sustained by the sufferings and endurance of Prometheus, would be annihilated if we could conceive of him as unsaying his high language and quailing before his successful and perfidious adversary.” That is to say, the point of the story – in Shelley’s estimation – would be lost if he were to copy the myth wholesale, and if he didn’t – in his own way – emphasize the importance of Prometheus’s rebellion. For this reason, Shelley took his perceived focus of the Promethean myth and recast it for a new age, bringing to the surface a moral depth and complexity he believes was already there. Adding new fuel to an old fire, as it were. Indeed, not for nothing does Shelley compare his Prometheus to Milton’s Satan, saying that the latter is the closest fictional approximation to the former – initiating conversation, then, with Milton’s ideas of political rebellion, as framed by classical works.

Indeed, that same concept of conversing could be applied to the entire work of Paradise Lost: that it is Milton’s attempt to converse with the author of Genesis, to elaborate and expand upon the themes he believes are already present in the Bible. As Milton says himself in the introduction to his epic, he aims to “justifie the wayes of God to men.” But what of other works that try something similar? Milton is surely not the only writer to attempt conversation with his predecessors. A similar framework of inspiration and influence is visible in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound – which was Shelley’s attempt at elaborating upon the themes he believed most important in Aeschylus’ plays of the Titan. Specifically, Shelley emphasized the rebellion of the Titan of fire against the king of gods and “Oppressor of Mankind,” Jupiter. But Shelley, like Milton, was not interested in merely copying and pasting his inspiration. As Shelley says himself in his Preface, the “moral interest of the fable, which is so powerfully sustained by the sufferings and endurance of Prometheus, would be annihilated if we could conceive of him as unsaying his high language and quailing before his successful and perfidious adversary.” That is to say, the point of the story – in Shelley’s estimation – would be lost if he were to copy the myth wholesale, and if he didn’t – in his own way – emphasize the importance of Prometheus’s rebellion. For this reason, Shelley took his perceived focus of the Promethean myth and recast it for a new age, bringing to the surface a moral depth and complexity he believes was already there. Adding new fuel to an old fire, as it were. Indeed, not for nothing does Shelley compare his Prometheus to Milton’s Satan, saying that the latter is the closest fictional approximation to the former – initiating conversation, then, with Milton’s ideas of political rebellion, as framed by classical works.

But both of these poems, Prometheus Unbound and Paradise Lost, raise their own questions about the nature of imitation in art, and what separates it from supposedly new creation – a debate that stands on its own as much as it is informed by the apparent line between quotation and conversation. At what point does the quoting of something – as Star Trek quotes Milton, as Shelley quotes Milton, and as Milton quotes Spenser – become something else entirely in conversation? Surely it is not enough to name-drop a favorite work – there has to be more depth in speaking with literary ancestors. Milton himself superimposed dialogue into a Satan that he ripped from various stories from the Bible – does that somehow disqualify his ideas as being genuine, making them unoriginal? Or does Milton do enough with his Satan to warrant his own place among the canon of Western literature – has Milton found his own pedestal in the arts? His myriad influences would seem to suggest so. Shelley in that same Preface of his speaks about the inherent imitative nature of poetry, calling it a “mimetic art.” He goes on to compare the great writers and poets of Western civilization (Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, etc.) in a line of continuous inspiration and cultural formation; they are “in one sense, the creators, and, in another, the creations, of their age.” Their works and their thoughts do not exist in vacuums; inevitably, invariably, they will draw upon their surroundings and their influences. If this idea is to be expanded upon, perhaps conversation arises when those influences are used consciously and with intent – with purpose that springs from the mind of the writer but cast in the shadow of its progenitors. (Perhaps, though, “shadow” is not the right word here – maybe “light” works better in such a context.)

But both of these poems, Prometheus Unbound and Paradise Lost, raise their own questions about the nature of imitation in art, and what separates it from supposedly new creation – a debate that stands on its own as much as it is informed by the apparent line between quotation and conversation. At what point does the quoting of something – as Star Trek quotes Milton, as Shelley quotes Milton, and as Milton quotes Spenser – become something else entirely in conversation? Surely it is not enough to name-drop a favorite work – there has to be more depth in speaking with literary ancestors. Milton himself superimposed dialogue into a Satan that he ripped from various stories from the Bible – does that somehow disqualify his ideas as being genuine, making them unoriginal? Or does Milton do enough with his Satan to warrant his own place among the canon of Western literature – has Milton found his own pedestal in the arts? His myriad influences would seem to suggest so. Shelley in that same Preface of his speaks about the inherent imitative nature of poetry, calling it a “mimetic art.” He goes on to compare the great writers and poets of Western civilization (Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, etc.) in a line of continuous inspiration and cultural formation; they are “in one sense, the creators, and, in another, the creations, of their age.” Their works and their thoughts do not exist in vacuums; inevitably, invariably, they will draw upon their surroundings and their influences. If this idea is to be expanded upon, perhaps conversation arises when those influences are used consciously and with intent – with purpose that springs from the mind of the writer but cast in the shadow of its progenitors. (Perhaps, though, “shadow” is not the right word here – maybe “light” works better in such a context.)

This, certainly – the concept of influence and commentary – was on the mind of Milton as he formed his poetic epic; not for nothing does he invoke the Holy Spirit in a manner reflecting Homer and the Muse; not for nothing does Satan seem to be cast in the role of Odysseus and Achilles. Influences abound in Paradise Lost – the conversation (along with the devil) lay in their details.

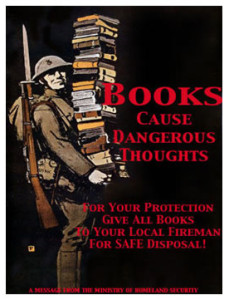

It makes one wonder if such conversations occur today, in contemporary literature. Surely they must – though few (writers and critics both) seem as sure as they once were. Without spending too  much time on it (for, indeed, I could spend another thousand and one words on this subject alone), the theme of conversation appears as a cornerstone in Ray Bradbury’s science fiction masterpiece, Fahrenheit 451. This 1953 novel, in brief, is the story of a futuristic society, wherein books have been outlawed as contraband, and are burned by “firemen,” a branch of the government designed to incinerate ink and thought alike. While one might be tempted to say that the crux of the novel is censorship – and, to be sure, that idea plays a part – a stronger argument is to be made that this is not Bradbury’s vision of a society of just censored thoughts, but of no thoughts at all. In fact, Fahrenheit 451 was his visualization of what society looks like when it stops thinking. Bradbury seems to be striking at a concept that seems very much inspired by Milton’s own fears: the elimination of thought outright. The characters of the novel’s society do not care that books are burned. They care only for the readymade, easily digestible reality they are fed on a daily basis – the illusion of thought transferred to them via television (Bradbury’s pick of intellectual poison). But as the reader comes to learn through the novel, the government did not wake up one day and decide that books were evil, abhorrent things. Rather, the government merely reflected and followed its society, a society that had itself grown to distrust books over time. A society that, in turn, was made up of individuals that had come to fear what books said and what they held and what they could do to people. As the chief of the firemen explains in the novel, our culture is in orbit around feeling happy at all times – titillated by transient pleasures, and fearful of anything that might puncture that happiness. That’s what makes books

much time on it (for, indeed, I could spend another thousand and one words on this subject alone), the theme of conversation appears as a cornerstone in Ray Bradbury’s science fiction masterpiece, Fahrenheit 451. This 1953 novel, in brief, is the story of a futuristic society, wherein books have been outlawed as contraband, and are burned by “firemen,” a branch of the government designed to incinerate ink and thought alike. While one might be tempted to say that the crux of the novel is censorship – and, to be sure, that idea plays a part – a stronger argument is to be made that this is not Bradbury’s vision of a society of just censored thoughts, but of no thoughts at all. In fact, Fahrenheit 451 was his visualization of what society looks like when it stops thinking. Bradbury seems to be striking at a concept that seems very much inspired by Milton’s own fears: the elimination of thought outright. The characters of the novel’s society do not care that books are burned. They care only for the readymade, easily digestible reality they are fed on a daily basis – the illusion of thought transferred to them via television (Bradbury’s pick of intellectual poison). But as the reader comes to learn through the novel, the government did not wake up one day and decide that books were evil, abhorrent things. Rather, the government merely reflected and followed its society, a society that had itself grown to distrust books over time. A society that, in turn, was made up of individuals that had come to fear what books said and what they held and what they could do to people. As the chief of the firemen explains in the novel, our culture is in orbit around feeling happy at all times – titillated by transient pleasures, and fearful of anything that might puncture that happiness. That’s what makes books  dangerous – they threaten our illusion of joyful ennui with hard thought and hard reality. “A book is a loaded gun in the house next door. Burn it.” the chief says. This is the world Milton feared and denounced, and the one that Shelley railed against as well; one that they hoped to combat with their writings. Can it be said that Bradbury was in direct conversation with Milton or Shelley? Perhaps not – they, admittedly, do not feature much in the novel, as far as direct references or quotations go. Yet the theme present in their works is continued in Bradbury’s: the idea of conversation as inherent, intrinsic – as utterly necessary – for meaningful literature (and good literature at that). Certainly the Bible (“Consider the lilies of the field…”) and Greek mythology (Antaeus, anyone?) play prominent roles in Bradbury’s piece. As one character explains to another in the story, the quality of information, the leisure to digest it, and the right to carry out actions based on what we learn, are the driving forces to literature – they are what fuel the very heart of humanity in literature, reflecting the very humanness of mankind. Was not this Milton’s focus? Books, or stories, can be good – objectively so – when they give man cause for thought. Thought – it should be added – not to censor or kill, but to converse with others, to examine one’s own worldview and morality and perhaps improve upon them.

dangerous – they threaten our illusion of joyful ennui with hard thought and hard reality. “A book is a loaded gun in the house next door. Burn it.” the chief says. This is the world Milton feared and denounced, and the one that Shelley railed against as well; one that they hoped to combat with their writings. Can it be said that Bradbury was in direct conversation with Milton or Shelley? Perhaps not – they, admittedly, do not feature much in the novel, as far as direct references or quotations go. Yet the theme present in their works is continued in Bradbury’s: the idea of conversation as inherent, intrinsic – as utterly necessary – for meaningful literature (and good literature at that). Certainly the Bible (“Consider the lilies of the field…”) and Greek mythology (Antaeus, anyone?) play prominent roles in Bradbury’s piece. As one character explains to another in the story, the quality of information, the leisure to digest it, and the right to carry out actions based on what we learn, are the driving forces to literature – they are what fuel the very heart of humanity in literature, reflecting the very humanness of mankind. Was not this Milton’s focus? Books, or stories, can be good – objectively so – when they give man cause for thought. Thought – it should be added – not to censor or kill, but to converse with others, to examine one’s own worldview and morality and perhaps improve upon them.

Bradbury’s idea of what books were – what they were and are meant to be – was that they are ideas in physical form, ideas meant to be shared, discussed, and debated by writer and reader alike. It is an idea expressed in similar fashion by Milton and Shelley – the arts are meant to talk to each other, to talk to us. On a divergent note, this notion of conversation versus quotation – the difference between conversing with a past writer and merely copying or quoting them because such is useful – raises questions about our current state of literature. Can it be said that the appropriation of works today is used in the same way as writers did in the past? Perhaps this is a generalization far too broad for a mere blog post, but I posit that there is, on some level, a difference between Shelley’s reworking of Prometheus or Milton’s generating his own account of Creation and some of the postmodern tales told today, like the retelling of Beowulf from Grendel’s point of view, or Hamlet from Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, or The Odyssey from Penelope. Do such works have the same (or similar) ideas in mind as Shelley with Aeschylus or Milton from  Genesis? Both men, along with Bradbury, emphasized the moral importance and imperative of their works; all three attempted to tease out the logical and moral implications of their characters’ decisions and wills – with, ultimately, a stronger understanding of human morality in the end. Can it be said that those novels by John Gardner, Tom Stoppard, and Margaret Atwood (among others) achieve the same end – are they even meant to? These are questions that may not have immediate answers – perhaps even comparing these works is not a worthwhile endeavor. That being said, there is something to be said about the seeming moral emptiness of some of those works – that postmodern sense of a reality that isn’t really there and truth that doesn’t really matter anyway. Milton never pauses in Paradise Lost to ask whether any of what he is writing is worth writing; Shakespeare, while great at subtle hints to powerful themes, never questioned if telling the story of Hamlet was itself a pointless endeavor. These men, to some extent, believed in their stories – not that their stories were literally true, necessarily, but that they had some kind of moral or social or spiritual purpose, that others may draw or benefit from them, either temporarily or for all time.

Genesis? Both men, along with Bradbury, emphasized the moral importance and imperative of their works; all three attempted to tease out the logical and moral implications of their characters’ decisions and wills – with, ultimately, a stronger understanding of human morality in the end. Can it be said that those novels by John Gardner, Tom Stoppard, and Margaret Atwood (among others) achieve the same end – are they even meant to? These are questions that may not have immediate answers – perhaps even comparing these works is not a worthwhile endeavor. That being said, there is something to be said about the seeming moral emptiness of some of those works – that postmodern sense of a reality that isn’t really there and truth that doesn’t really matter anyway. Milton never pauses in Paradise Lost to ask whether any of what he is writing is worth writing; Shakespeare, while great at subtle hints to powerful themes, never questioned if telling the story of Hamlet was itself a pointless endeavor. These men, to some extent, believed in their stories – not that their stories were literally true, necessarily, but that they had some kind of moral or social or spiritual purpose, that others may draw or benefit from them, either temporarily or for all time.

Ultimately, the difference between conversing with other writers and artists and quoting them appears to be this: in conversing, there is a genuine appreciation for the work, whether its flaws or acknowledged or not. There is a recognition, however overt or subtle, that the work being referenced has merit in its own right, as a piece of writing or literature or fiction worth deep consideration. Shelley and Milton took the story of Prometheus and the story of Creation and wanted to tell a new narrative from them; thusly inspired, they set out to make their own points known, taking what they believed was already present in the story and stretching it further. What these disparate points serve to make here is an attempt – on my part – to understand the nature of conversation of writers in literature. Conversation matters because conversation makes for a greater work, in that it builds off points brought up by others and makes something new. Things are refashioned and remixed – but respected as well – in such a brew: a new work rises from the mixture of the old. Quoting, meanwhile – quoting seems to be the lifting of a concept because it gels well with a point one is trying to make, but is not irretrievably linked to it – not fundamentally tied to its predecessor’s themes. To be sure, Fahrenheit 451 is chockfull of quotations and allusions and references to other writers; yet, Bradbury seems to be, in his own way, in conversation with these other writers – if not with the authors themselves directly, then with their themes, the ideas that drove them. Bradbury has nothing but respect for the power of not just narrative, but of story, of tales with meaning and purpose and inspiration. Rather than taking old stories and emptying them of their moral content, leaving them as either husks or filling them in with the passions of the day, Milton, Shelley, and Bradbury sought to reinforce what (they believed) was already there, strengthening the very themes that inspired them. In this does conversation become a vehicle for reciprocity – not just a mirror, but a microscope, expanding and focusing in on the same or similar image. The questions then fall to us: how do we, as readers, attempt to graft the themes of these works into and onto our own lives, incorporating their passages and their messages into our own personal languages and vocabularies, our own sense of who we are?

At any rate, though this post is hardly definitive as a point, and still at work as any sort of thesis, my time with my “Spenser and Milton” class has helped me better understand this concept of conversation. The professor and fellow students with whom I – to use no better word – conversed taught me much about the nature of conversing. In the end, it seems that conversation is – to return to the title of that episode of Star Trek – a matter of seeds. How those seeds are planted – whether they fall on paths for the crows to eat, or in shallow ground, or in thorns – that is what matters for conversation. Is the work you write speaking to, or with, someone else? If such a seed of thought falls into good soil, sowed by inspiration, and watered by others along the way, it may just grow into something that is, strangely, the work of many, yet of one – a product of inspiration, meant to inspire others in kind.

Perhaps, then, for this particular topic, one question needs answering before the rest: Have you ever read Milton?