I am teaching a course in the poetry of Edmund Spenser and John Milton to students at the University of Michigan-Flint. The course attempts to expose students to the idea that the English literary tradition was built by pens and heads sitting by their studious lamps, musing, searching, revolving new notions, and having intense conversations with their beloved dead predecessors. Spenser loved Chaucer and Virgil and Ovid and Plato. Milton thought the “sage and serious poet Spenser” to be a better teacher than Scotus or Aquinas—because by following his characters through the thickets of fairyland, the reader gained practice reasoning and interpreting which is, essentially, about making choices; what better resource for learning to navigate the involved paths of the fallen world than “books promiscuously read?” “Dr. Kietzman, can you look at the word on page 48. What language is that?” The student is pointing to a word in lower-case Greek script which translates as “enthusiasmos” or inspiration. Most of my students are finding the initial dip into Spenser to be “all Greek.” “Who is Virgil?” “Is there a book that can give me an understanding of the back stories?” They don’t know The Aeneid or why Dido is such a controversial and problematic figure in Aeneas’ history? I simplify it for them: public duty divine calling … GOOD; private love, passionate affair … BAD. This makes them laugh. Suddenly, they are asking questions and they want to know more. I realize in a flash that my class is probably the closest most of these bright and perceptive people will come to a classical education, and the most I will be able to give them is a crude topographical map, marked with directions, major civilizations and the authors that “put these nations and their values on our map,” and tell them merry tales from Ovid that all the English poets repeated. We are in Flint, a city at the top of the “misery index,” and one of my colleagues asserted in a department meeting last semester that what I teach is not “relevant to students’ occupational objectives,” yet I see them awakening. It may be grandiose to think of what we are experiencing as a Renaissance, so let’s think of it as a Ruinassance, wondering through fragments of the past scattered along the densely allusive lines of Spenser, who spent his writing life in the exile of southwest Ireland, and Milton, who finally got around to using his talents when he was a blind war criminal, a regicide, blessedly overlooked by the restored Stuart regime. Maybe they are not so unlike us after all except in their enthusiasmos which are like springing fountains; and my students eyes light up when some drops of “holy water” fall upon their heads.

Spenser and Milton were living in dangerous and disordered times. When we hear the word “Renaissance,” I think we imagine some golden world of art, theatre, and literature. But England saw itself differently as a marginal, rogue nation with no empire and no ability to compete with the big boys of Europe (SpainandFrance). Both English rulers and English writers linked material insufficiency to spiritual strength. For Spenser, in the wilds of an Ireland whose chiefs staunchly resisted the English attempts to settle colonists on plantations, the Renaissance was also a Ruinaissance, a sifting through the residue of the classical tradition, and raking in the ashes of English in order to remember the cinders of his heritage. Spenser set about to claim the kingdom of his own language; and he incorporated words from the “Old English” dialect spoken in the Pale by earlier Norman settlers and he incorporated words from Scots and Gaelic as well as classical languages. Spenser made writing out of loss. Why cannot we do the same?

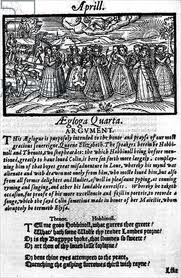

In “April” the shepheards remember one of Colin’s greatest hits which he sung to Eliza before he fell in love with Rosalind.

We’re beginning the semester with the first great works of both Spenser and Milton, which happen to be elegies. Students have little experience with this form (when I asked, none could cite any elegies that they especially liked) despite the fact that elegy is concerned with issues so necessary to our lives. I don’t think there is any other literary form in which words do such important work. They enable the writer and reader to grieve, to express anger, to question the gods, to remember lost ones, to come to terms with our shared mortality, and to tap into the wellsprings of our own creativity. What elegy teaches us is that we must accept and enter into our own deepest pain. If we tap into that, we tap into our creative life. How is this not relevant to our students? Pain is everyday. Pain is all around. I learned last semester that the general disease our students suffer from is a lack of encouragement, time, and inspiration to express themselves creatively. The hours on Facebook are not enough. Screens are not the solution. Maybe Spenser and Milton have something to say to us that still that is deeply relevant about human growth not despite but from the pains and frustrations and losses of our lives. Maybe Spenser and Milton help us understand how learning to love—really love—is learning to mourn.

Pan, the God of shepheardes and inventor of the “Pan pipes” made from reeds (the nympth Syrinx begged to be metamorphosed) and she was turned into reeds which Pan plays! Weird and weirder!

Spenser’s pastoral poem, The Shepheardes Calendar, is not an elegy occasioned by a particular death, although his poetic persona, Colin Clout, the lowly shepherd boy, is complaining about having fallen in love with a girl who rejects him. As we move through the months of the year—January to December—we hear about how great a poet Colin was until he saw “a sight that bred my bane” (Rosalind) and understood for himself “that love shoulde breed both joy and payne.” The other shepherds try to console him and lure him back to the activities that once gave him pleasure: reminding him that their pastoral world is a paradise, that the world needs his poetic gifts, remembering songs he sung and the sight of the Muses running to hear him pipe. Colin refuses to sing: what’s the point of poetry? What point is there in writing or singing when it doesn’t get you girls, earn money, and when there are no “jobs” for poets? Besides, says Colin (I’m paraphrasing), all the great poets are dead! Spenser has Colin specifically grieve over the loss of Chaucer (“The God of shepheards, Tityrus”) who is “dead” but who was “the soveraigne head / Of shepheards all, that bene with love ytake; / Well couth he wayle hys Woes, and lightly slake / The flames, which love within his heart had bredd,”. Believe it or not, one of my students (who is currently taking Dr. Larsen’s Chaucer class) had his book of dream visions in his hand, and made the right connection to a poem in which Chaucer’s narrator is a lovesick insomniac who reads Ovid to distract himself from woe, learns from the Roman poet that there is “a god of slepe” to whom he prays, promising lavish mattresses and silken coverlets, and falls asleep to dream a dream which he describes as a “wonder thing.” I digress (as I often must in class), but returning to Colin: we finally hear him sing when invited to sing an elegy for Dido, the Queen of Carthage who killed herself after Aeneas’ abandonment. Colin does what the duty-bound Aeneas did not do, he mourns for Dido (like Chaucer before him); and within the limitations of his former lament, he recognizes a usable truth: if the “state of earthlie things” is, as we experience it, trustless and unsure and governed by Mutability (personified at the end of the Fairie Queene as an electrifying and energetic goddess), death is just the big change when “soule [is] unbodied of the burdenous corpse.”

“Is Colin wasting his time with love?” a student asks. “Is love destroying him? Is it preventing him from singing as sweetly as a swan? Maybe. Many of the characters in his rural world think so. But the wise old shepherd, Thenot, offers a valuable perspective on the long term project that is human love:

Ah fool, for love does teach him climbe so hie,

And lyftes him up out of the loathsome myre:

Such immortall mirrhor, as he doth admire,

Would rayse ones mynd above the starry skie.

And cause a caytive corage to aspire,

For lofty love doth loath a lowly eye.

There are so many messages to help my students: these fictional voices from the great poets of the past whisper, “all you have been through and all you are going through is not accidental and pointless, but part of the living force that is within you, within us, your struggles were our struggles.” We created consolations for ourselves, resolved our mourning, and discovered reasons to sing. You can, too.” Their submerged messages touch gently our “trembling ears” and we read on and sometimes risk writing a response. As we listen, we unconsciously accept their proffered companionship and feel less alone with such spirit guides who talk every time we open their books, now ours, and pronounce their words in our mouths (because “you can make sense of it more easily when you hear it”). The ear is a better guide than the eye in these foreign worlds where the spelling is “weird,” where there was no “spell-check,” and where “eke” means also.

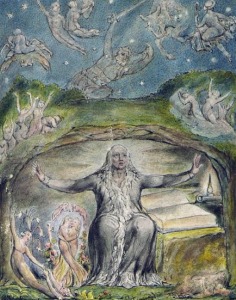

I find myself constantly reassuring students that, as the sun of understanding rises to stretch out all the hills of new found lands, they must not be afraid. “We cannot know all that they knew.” We just have to find and love an oak, a stream, a rock, a cloud, or (in Chaucer’s Book of the Duchess) a puppy or a melancholy stranger. As in life, we must find and cling to things we can love. We must stay with them long enough to understand their power or let them lead us to fresh groves and pastures new. It is crucial that students have the experience of their own limits and that they accept their limits. The experience of limitation is our human ID card and the natural sense of loss and impurity we bring into the world our Passport. It is a wonderful thing to be the witnesses of worlds we could never have made. It is a wonderful thing to honor poet-makers and, by extension, great creating Nature by whatever name we know He or She. The world transfigured on a page is as wonderful as the world revealed to Job by God when he speaks from the whirlwind, but the worlds inside us that we glimpse in these mirrors are also wild lands full of well springs and streams. We receive the most satisfying refreshment when we bow down and taste the cold waters of these internal springs.

As teacher, I am also mother and travel guide. I know quite a bit more than my students do, but what I reiterate over and over is that I, too, am learning. I tell them what I believe: that comprehensive knowledge is not the point, that their songs and discoveries along the way are what matters most of all. We must use the material we’re studying to make our own “mery tales” or sad tales. So we sit together in 456 French Hall and we talk and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh at silly shepherds, and speak of Elizabeth’s court, and hear the rumors of turning political tides, imagining the future when John Milton will yet once more argue passionately that all Kings be held accountable. We are God’s spies, and we accept Milton’s definition, lifted from Scripture, of Truth as a streaming fountain; “if her water flow not in a perpetuall progression, they sick’n into a muddy pool of conformity and tradition. A man may be a heretick in the truth; and if he believe things only because his Pastor sayes so, or the Assembly so determines, without knowing other reason, though his belief be true, yet the very truth he holds becomes his heresie.” We must humbly accept our smallness in the presence of such teachers, and we must take the freedom they offer to reach and grasp and build with those blocks we can reach, trusting that in time, our arms will lengthen, our desire deepen, and our minds grow. Growth happens in strange ways though. I don’t think we can grow students’ minds by writing more detailed syllabi or giving them more assignments. We must give them time and space to be spontaneous. But most of all, we must trust them. We have to mourn our own lack of talent, education, time, teaching techniques, and the failures of our efforts—in short, we must face our hopelessness; and it is this which seems to allow the redeeming force to come into play.

Milton’s elegy Lycidas, written on the occasion of a fellow student’s drowning in the Irish Sea, gave Milton the chance to find his personal voice and discover that its most powerful expression may be that of witness.

Please accept this heartfelt sketch of what I think I need to do as a teacher. If it seems like a mass of fragments, my excuse is that I am a student of the Ruinaissance in love with the words and lines, sounds and visions I find. Preparing to teach “Lycidas” next week, I read over morning coffee Stanley Fish’s summary of the problems critics find with the poem which has been described as “an effort to bind and clamp together a universe trying to fly off into separate bits” or “an accumulation of beautiful fragments.” Milton understood his smallness and he appreciated the power and the wisdom of the voices he heard in his books. His work achieves individuality by witnessing and paying tribute to his complex loves and to his love of study. “Lycidas” begins as will so many of his prose tracts with the apology that he is unready for a task he is being asked to perform before his gifts are mature. We are called to the same task.

Building the Temple of God in the Ruinaissance of Flint,

Mary Jo Kietzman