In Defense of the Humanities

The graduate with a science degree asks, “Why does it work?”

The graduate with an engineering degree asks, “How does it work?”

The graduate with a management degree asks, “How much will it cost?”

The graduate with an arts degree asks, “Do you want fries with that?”

For humanities majors, does a joke like this make us laugh or make us angry? As with most jokes, there may be some unfortunate truth buried in it.

Americans believe that a college education is the best way to get ahead in life. A college or university degree is synonymous with increased status, both social and economic. However, not all diplomas are created equal. As the opening joke suggests, graduates with humanities degrees are the butt of jokes and experience social discrimination. Math and science degrees are, however, respected in an America gripped by the newest economic downturn—probably because they hold out the vague hope of restoring America’s hard science edge. With an economy that’s been in slow decline for decades, it isn’t clear how reading and studying literature, which in its very structures and ways of speaking, expresses a vision of value and of life incompatible with those expressed in economic or political science texts, can help individuals or help our society. Why study humanities when engagement with them stimulates our desires and trains our imaginations for life worlds that subvert science’s norms of rationality? Is there a place for humanities majors in the modern world?

Of course, the typical response to this question involves two words: job security. We’ve all heard them before. For many Americans, job security is the primary motive for making decisions, especially about which career path to pursue at university. For individuals interested in language, literature, and the arts, job security has always been elusive but, blessedly, of secondary concern.

Jessica B

I chose the English major because I want to write and edit. Since I made my choice (before I’d even started college), I have had loving friends, teachers, and family members express their well-meaning concern.

“You won’t make any money that way,” they would say.

“I just want you to be able to take care of yourself.” That was what my father would often say to me. He wanted me to have a fallback, some kind of secure job. It was around then, however, that Flint’s economy really collapsed and the factory jobs upon which our city had relied were leaving. My father was still concerned, however, that I would end up on the streets, until I firmly stated, “Dad, there are no secure jobs anymore. I would rather risk financial comfort and be happy than risk financial comfort in a job I don’t love.” My father hasn’t stood in opposition since.

It wasn’t until college that I decided to tack on the words “and edit” when telling others my dream career. Telling people I want to “write and edit” gets a much less negative reaction than simply telling them I want to write. Editing offers stability and for some reason, an office-type job in an office-type environment seems to others a much more practical career goal.

It’s not that I don’t love editing; I love picking apart prose and figuring how to make it work better. I also love the idea of helping intelligent people communicate their ideas skillfully. My true passion, however, lies in writing. I have the audacity to think I have been through interesting things and enough boldness to think others will care to hear about those things. I also have just enough insanity to think that my experiences could change the lives of others; I know they’re changing mine.

Stephanie S

I’ve been worried about my future as an English major. I had a 34-year old co-worker who has his master’s degree in linguistics and was working at McDonald’s. He finally got a job substitute teaching, but he can’t seem to make use of his degree in this area. He also doesn’t want to leave because he has to take care of his parents. Before they lost their health, he was teaching in Turkey and Poland. He told me that my best chance at finding a job in this economy would be to teach in other countries, though I had already decided I was going to do that in the first place.

Eventually I do want to get my master’s degree, but for now I plan on teaching English as a second language abroad. If I ever decide to return to the states for more than six months at a time, I may have to find something more permanent to do than just substitute teaching. I’d like to one day have the wisdom and intellect required to be a professor, whether I am one here or in another country. Everyone always asks me if I want to teach elementary or secondary school here in the states, but if I’m going to make lower-middle-class wages anyway, I’d rather travel the world while doing it. At least then I will feel fulfilled in some way, as I’ve always wanted to travel.

Both of these accounts underscore the current of public skepticism toward the uneconomical humanities degree. When English majors have to set their sights on jobs overseas, it’s painfully obvious that the climate in America has changed. We’ve long been accustomed, as Martha Nussbaum points out, to thinking of the humanities as optional: “as great, valuable, entertaining, excellent, but something that exists off to one side of political and economic and legal thought, in another university department, ancillary rather than competitive.” Today, however, there seems to be increasingly open hostility. Americans simply do not have time for “fluff.” We’re too busy trying to earn money and satisfy our hedonistic desires. Courses of study that train our imaginations and feelings are viewed as downright threatening. Many students report that if you tell somebody you’re an English major, the response you’re likely to get is, “Oh – are you going to be a teacher?” The question itself is insulting since the subtext screams: “what else can you do?”

Victoria S

Someone once asked me, “What do you want to do with your English major?” I told them how I wanted to get my secondary teaching certificate (high school), and work my way up to university level. I told this to someone I really looked up to and respected, and their response crushed me. They said, “Teaching is just the easy way out. In any field teaching is always the easiest and requires the least amount of schooling. Anyone who is a teacher is simply lazy and couldn’t work their way through to a more important job.” I can’t tell you how many times people have told me that I picked a skill with no money and no value. For me, English is something I am very passionate about. It is how we communicate – how we can connect with those around us. I want to be able to share this with other people. THIS is why I want to be an English teacher.

In the face of public scorn, humanities majors are going to have to develop thick skins. But maybe, if we read between the lines of such degrading comments, we can find reason to take heart. Consider this: if literature is, from the perspective of the general public, deserving of suppression, maybe it is no mere frill. Maybe it has the potential to make a distinctive contribution to our public life. Victoria notes that English is integral to the communication of individuals and of society more generally. Human beings long to connect with one another. This is a truth proven by things like Facebook and texting, even if they are both quite new.

Yet those forms of communication don’t touch people on the same level as music, art, writing, or even a deep and mutually satisfying conversation. In a society that is clearly searching for meaning and connection, maybe we’ll find that there is a need for people who can skillfully read and use language and media arts.

Sarah E

Professors and professionals in various fields maintain that American job applicants lack writing skills. It’s not that surprising if you think about it. Here at UM-Flint, to get a degree in almost any major, with a few exceptions like English and education, you only have to take two English classes and have a very small number of humanities credits to graduate. In many majors, critical thinking and analysis in the form of reading and writing is barely used; yet this is a skill that is necessary for almost any job. People dog on how the humanities are “soft studies,” but when we humanities majors enter the workforce, we won’t be the ones lacking writing skills.

This problem has become so prevalent that now classes having nothing to do with writing are trying to incorporate it. In my BUS 115 class, we had to do an 8-to-10 page research paper. Sounds like a good way to incorporate writing, right? Not so much. The class emphasizes learning programs like Excel, PowerPoint, and Access, and these programs were not integral to the paper. The paper itself could be on any topic, even one not business-related, and was essentially just a plug and chug from the internet experience. The idea of writing for classes is great in theory, but just shoving some half-concocted project in the mix doesn’t teach very many writing skills.

It appears that our society may need the skills of the humanities more than it thinks. In the short term, however, statistics suggest that graduates with humanities degrees may have to suffer a lack of gainful employment.

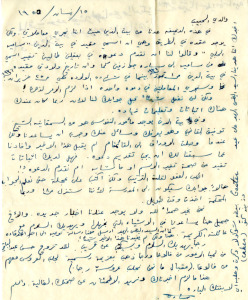

English cursive is almost a lost art that will soon appear as foreign as Arabic script.

Bob G.

The top ten occupations that employ persons with a bachelor’s degree in English are:

1. Artists, writers, broadcasters editors and public relations. 10.7%

2. Administrators, executives and middle managers. 10.6%

3. Secondary school teachers. 10.6%

4. Insurance, real estate and business services. 5.9%

5. Secretaries and administrative assistants. 5.1%

6. Sales. 4.9%

7. Other management positions. 4.8%

8. Other administrative positions. 4.8%

9. Elementary school teachers 3.5%

10. Service occupations 3.2%

(Source: United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics)

According to my English-major math skills, that reflects a 35% unemployment rate for English majors! As always, there are two ways of looking at these stats. Is our glass 65% full or 35% empty? I became an English major because I enjoy reading literature, and I enjoy writing about it. I would like to teach in the future and I’m not insulted when others ask if that is what I want to do.

So, what can we say when someone insinuates that our English studies are not relevant? A quick punch in the face is probably a poor reaction, so we’d better find a more appropriate answer or answers. Perhaps we could say, “English and the humanities provide an insightful understanding into moral, ethical, political, and ideological forces.” On second thought, that might be showing off.

I suppose, as with most everything in life, there are two ways to approach the career outlook for English majors. Either we are not terribly bright for choosing a major with such a dim employment outlook, or we are extremely passionate about our major. I like to think it is the second choice, although I cannot control the perceptions of the rest of the world.

Indeed, job prospects are grim. That’s no easy problem to fix. However, maybe the remedy starts with what appears to be the force driving students into humanities: their exploration of what makes life meaningful. There is, after all, more to life than work; and passion must count for something regardless of occupation.

Josh L

I think I have been taking writing seriously for about 12 years now. It all really started during my senior year of high school. I ended up taking an English 101 class at Mott and it pretty much changed how I looked at writing. I can remember my teacher telling us “Forget everything you learned in high school. Forget five paragraph themes. In true writing you should be concentrating on content, not borders.”

After that class I also started playing in a band, which led to writing songs. I was horrible at first, but eventually I learned how to write lyrics in a poetic form and create well thought-out melodies and chord progressions. It was during my early years playing as a musician and not attending college that I really started to experiment with writing.

I also used to be on an old social network called LiveJournal. It was on this site that I started writing in a lot of different formats. Poetry, short stories, automatic writings, lyrics, even a few rants made it on there. The point for all of this is that writing was always a great outlet for me to get my feelings heard, even if know one was listening.

Corynn B

I knew I wanted to become a teacher when I got involved in student teaching for a 5th grade classroom. I fell in love with not only the kids but the career. I looked forward to seeing those kids, looked forward to thinking of fun ways to teach them new ideas and concepts. English had always been a creative outlet for me, especially in sensitive subjects, and I wanted to give that gift to my students. Reading, writing, and immersion in the lives of others through fiction are great ways to release the emotions we tend to keep locked up.

Then, during my first year of college (August of 2009), I was diagnosed with cancer. They caught it fairly late, already in its third stage. I had no choice but to go through the motions: surgeries, medicines, and weakness week after week. Yet I didn’t miss a semester of class and finished my treatments by the following spring. Now I work full time as an assistant manager in a retail store, along with being enrolled in school full time. As if that’s not enough, a month after I began class, I went into the doctor with pains and persistent illness. After a week of painful restlessness, I got the news. The cancer was back, only in the first stage this time, Yet the chemo medications were a must. Now I struggle with constant weakness, especially between doses, and feeling like my body is ready to collapse.

True, some days are harder than others, but I have a strong support system of friends and family. What really keeps me going though is the image of teaching English in my own classroom someday, teaching kids to learn and love the creative outlet that I am using right now in order to reach out and express my story. English isn’t just a subject to be taken lightly. It’s what makes us human, and it’s what connects people on a different level than any other subject.

“Forms of Composition”–an original painting by Corynn B. “I wanted to prove that composition is not just simply writing; it has many shapes and forms and outcomes.”

Students in humanities fields learn to find and express the value of being alive, and they also become aware of the persistent forms of human need and desire that are common to individuals across time and geography. The human condition is such that we are not satisfied by mere scientific algorithms and mathematic proofs. No, our guts yearn for more; life must be meaningful! Students who read novels and histories, epics and drama are exposed to the shifting social, cultural, and political forms of life that facilitate or suppress human flowering. Dan S., a math major who works as a computer programmer, is currently taking a class in literary analysis. He is uniquely positioned to see the ways the tech environment—or any professional environment, for that matter—can drain the spirit. His story addresses the primal need within us for language with cadence and rhythm that will move us.

Dan S.

I remember the first time I spoke to a computer and made it do exactly what I wanted. It was magical. I felt like I had such power at my disposal. I was in awe. Years later, I find myself writing software professionally. I spend my day writing data schemes, authoring widgets, refactoring code and optimizing query. What a mouthful. I couldn’t even begin to explain what all of that means in layman’s terms, and frankly I wouldn’t want to.

There was a point when you couldn’t get me to shut up about my latest coding project. I’d drag my family in front of the screen to show them my latest creation, and they would politely patronize me. What seemed like a nerdy hobby to them became an obsession to me. Like a mad scientist isolated in his secret laboratory, I would spend my nights typing away on my computer. Some nights I would be creating a video game, enveloped in a world limited only by my own imagination. I had the power to construct a world down to the tiniest details. I could define a hero’s strengths and flaws, create a conflict that resonates with the player, reward them with treasure or punish them with death. On other nights, I would feel the urge to take up some ridiculous mathematical challenge, such as which prime below one million can be written as the sum of the most consecutive prime numbers (41, if you’re curious). I was amazed that with a little scratch work and a computer to crunch the numbers, I could solve math problems that seemed incalculable.

At some point, though, everything changed. Technology ceased to be my artful expression, and it became a bulleted list on a resume. I traded my passion for a desk job where I perform routine, monotonous tasks. Occasionally that old spark still finds its way into my work, but those moments are rare. As I mature in my career as a developer, I see a lesson reflected in Walt Whitman’s poem “When I Heard The Learn’d Astronomer”:

WHEN I heard the learn’d astronomer;

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me;

When I was shown the charts and the diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them;

When I, sitting, heard the astronomer, where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon, unnacountable, I became tired and sick;

Till rising and gliding out, I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

All of us fall in love with something. The speaker here fell in love with the mystery of the universe. Sometimes we reach a point where our passion is reduced to proofs or figures and we just become sick of it. Like the speaker in this poem, we have to put ourselves back in a position to fall in love all over again. When in a business atmosphere, time and energy tends to be devoted to tasks that can be monetized. Sometimes I have to step back and code something that is completely pointless. It will never go to production and I will never see a cent from it. It is an act of artistic expression. It is my personal responsibility to wander off on my own and find that perfect silence. This artistic exploration is essential to keep our humanity, to keep that creativity alive. If I lose that passion, that awe that I fell in love with, I am no more human than the computer at my fingertips.

Dan’s perspective exemplifies why pursuing the humanities is valuable and necessary to a healthy society. It’s not that the arts and sciences are rivals; quite the contrary is true. Their passions and pursuits are antipodal fuels, resources different but equally precious. The great people of history have emerged from worlds where a basic education taught and valued both. Even the United States Congress, in founding legislation for the National Endowment for the Humanities, stated, “An advanced civilization must not limit its efforts to science and technology alone, but must give full value and support to the other great branches of scholarly and cultural activity in order to achieve a better understanding of the past, a better analysis of the present, and a better view of the future.” Source: http://www.neh.gov/whoweare/legislation.html.

Paul F

I used to work as a third-shift stocker in a grocery store. It was the worst year and a half of my life so far. Six nights a week, I spent 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. in a state of mental isolation, while I filled the shelves with cleaning products, cat food, baked beans and the like. There was no outlet for my intellectual capabilities. Since I have only ever truly belonged in academia, this was maddening. I regularly wondered about the successes my old high school classmates were having in state universities, while I withered away in directionless loserdom. Physically exhausting work and the odd hours made the situation that much worse for me.

Then that spring of 2008, I started climbing out of the depression I had fallen into by reading books during my 2:30 a.m. lunch breaks. First came Ship of Fools by Katherine Anne Porter. It was the first book I’d read in two years, and I found it quite appealing, its prelude to war and the lack of a protagonist especially. Then a friend gave me Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead for my birthday. That book really blew me away. Its main character, Howard Roark, gripped me and became a source of inspiration through his bold actions and unyielding motives. Roark’s ideology and Rand’s concepts carried me through the most harrowing and mundane nights on the job as I engaged in literary reverie.

Examining the person I am today and seeing how far I’ve come from being a distressed young man, I see that I am infinitely indebted to The Fountainhead. It helped me when my world was reduced to nothing but numbers – how many cases I could stock in an hour, how much money I was making, what time I’d finally make it to sleep in the morning.

JoAnn Z

We all need help finding our way sometimes. Even in my Literary Analysis class, I was struggling to enjoy the poetry unit. I had to write a five-page paper and liked William Butler Yeats’ poem, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.” Even after I studied the rhyme pattern, analyzed the alliteration, and understood what Yeats was trying to say, I wondered how I could write five pages on this short lyric. Taking a break to watch some videos a friend had posted on YouTube, I wondered if anyone had made a video on Yeats’ poem. I typed in the title, and what happened next was amazing! I watched this beautiful video of what Yeats described in the poem: a small cabin, lake, birds, stars, bees, purple flowers. Someone had set images behind the printed words of the poem, and they played Irish music and chirping birds in the background. I was alone in the room, so I read the words aloud … in an Irish accent. I was transported! I could see images instead of words; hear chirping instead of reading about birds; and I finally embraced the poem the way I imagined Yeats felt when he wrote it. Now when I close my eyes, I too “will arise and go now.” I just needed some help to find the passion. As I said before, we all need help finding our way sometimes. The wonderful thing about the humanities is that it never lets you forget who we are – all just struggling people on the planet. It is this realization which is needed most but is unfortunately valued least. This fact alone will make little difference to us. We can intellectualize about education’s failures, but in the final analysis, it is the creative inspiration which drives us on.

Understandably, these accounts will not sway all humanities naysayers. Common wisdom suggests that marketable skills are more important than ever due to the loss of American manufacturing. The study of English and the humanities bequeaths unto us a grand ability for introspection and reflection – but what good are those if we can’t make a decent living?

Bob G

Some critics want me to believe our liberal arts education is irrelevant, as it does not prepare a student for the world job market. Maybe they are right in that respect. In an increasingly automated world employers are demanding more technically skilled workers. I wonder if that is what our lives have become. Are we willing to base our whole lives on acquiring skills to build more machines to replace people? Are we willing to make ourselves slaves to technology? Sometimes it appears that way. There is a huge push with schools to “prepare students for the job market.” A noble goal? Perhaps, but I believe the world and the human race would be better served if schools prepared students for life rather than jobs.

In our quest to legitimize our humanities studies I think we fall into a trap when trying to explain which jobs our English degree will prepare us for. By studying the humanities we learn how to live life and serve others, not how to become slaves to an inhuman, mechanized society. If we try to argue that humanities studies are just as important as vocational studies and we base success on our monetary value to society, we will fail.

There is a place I know where the humanities have always taken a back seat to the technological: the United States military (or any military, I suppose). How does this philosophy affect the lives of the participants? In war (I hesitate to use the term since our last war officially ended in 1947) one’s thoughts become reactive instead of proactive. “Do as you’re told” replaces “think for yourself.” Survival replaces living. The daily moral reality for many infantrymen on the battlefield becomes, “Better to be judged by 12 than carried by 6.” Soldiers become robots; slaves to the military-industrial complex, the largest technology based company in the world. Is that really what we want for our civilian lives as well? Shall we measure our success by how much we’ve contributed to our own destruction?

If we use empirical data to compare the humanities and the sciences it is easy to see how some people might consider the sciences superior. The good that comes from the study of humanities is a bit more difficult to measure. Some people tend to view the two camps as opposites. Would society’s conclusions be different if we used antonymous words to describe the two areas of study? How would the argument change if the two disciplines were called “humanities” and “inhumanities”?

Perhaps our society has its priorities out of order. Certainly, there is as much work to be done in the social field as there is in the practical/scientific field. We still don’t seem to understand how human people and human societies work. There are so many unknowns. Doesn’t it stand to reason that pursuing humanities fields will help us diagnose and imagine cures for social ills. Moreover, it has been said that the best way to change the world is to begin with ourselves—to create life, each of us needs to become more fully alive, more fully human.

Jake C

Degradation of the humanities erodes the cornerstone universities build on – diversity. Knowledge in the humanities helps people make sense of how others are, and helps infuse individual lives with intangible necessities. Take away religious studies and a university loses the ability to explain the anchor of so many students’ morals and lifestyles. Take away art and a university denies a student self-expression and feeling. Take away history and a group of students loses the stories that make them who they are and shape the world we live in today. Take away political science and students have no knowledge on the workings of government and the rules that they have to live by. Eliminate English and all the great stories that society shares are gone – those bonds that help connect us vanish. Take away music and dance and we lose the inner strength and multi-dimensional talents that students have. Take away the humanities altogether, and a college loses its color. It might as well become a prison. There will be no voices, just drones focused on economic survival.

We must work toward changing the public perception of the English and the humanities. Since the gains afforded by practicing critical thinking and philosophy are difficult to quantify, this will be a difficult task. As Americans, we face a world increasingly dominated by numbers. At the same time, our nation is crippled by economic crisis and political strife. If the drawn-out recession isn’t enough, the formations of both the Tea Party movement and the Occupy Wall Street protests ought to tell any sensible citizen that our country’s current approach to existence deserves serious inspection. Manufacturing jobs fleeing the states are also a game of digits – but what’s worse is that they represent our lost humanity. A large swath of Americans have lost not only their livelihood, but their personal esteem too.

We must get away from a numbers-dominated culture. But how? The answer lies in staying positive. Bemoaning the lack of acceptance by our peers will help nobody. Humanities students can’t fight fire with fire by reflecting the blame of uselessness at our accusers either. Worse yet, we can’t buy into the mocking assessment laid upon us by the camps of hard science.

Bob G

Sometimes I notice English majors tend to join in on the English-̶̶̶̶major bashing, accepting the “fact” that our chosen degree is less important than others. In order to convince our peers that an English degree is a useful degree we will first need to conquer our own ‘little brother’ perception of ourselves. It is a tough case to defend if you don’t truly believe it yourself.

To be taken seriously by others we MUST take ourselves, our degree and our language seriously. At my age I still gravitate toward newspapers for my daily news. I find that there is something about the feel of the pulp and the newsprint that is relaxing. In my morning news gathering I find numerous spelling and grammatical errors made by journalism professionals. Apparently, the details of their craft are unimportant, at least to them. For me, that is a sign that they don’t take their language or their profession seriously. If we don’t take ourselves and our craft seriously why should others? More pride in our craft and our output will cultivate more approval and acceptance from outsiders.

So, what good is an English degree and what can we do besides teach? I say we can do anything we want to do. Creatively prove that you can bring value to a company. We analyze simple ad complicated texts from a variety of times periods and find fresh and innovative ways to understand them. The question is can we find ways to apply our analytic skills so they have practical value in the workplace? I believe many English majors possess creative, flexible minds that can offer fresh approaches to a multitude of situations that may arise in the workplace. I would like to think that, as we progress through our major, we learn something more transcendent than simply “readin’ and ritin’.” It is your responsibility to prove to the world that these talents are relevant and to be respected. If we continue to think it’s not a big deal because we used a semicolon where we should have used a colon, then, shy should anyone else care? If you were a passenger in my helicopter, was I still flying, and I adjusted cyclic pitch when I meant to adjust collective pitch; it would be a big deal! That may be a poor example because of the life or death circumstances, but if you truly believe in your chosen field of study, you should take it THAT seriously.

And so we stand humbly before you, willing to sling fries and burgers in order to continue in our field of study. We are passionate and dedicated, striving to convince the outside world that we are valuable. The perception that science and math are more difficult than literature and philosophy is a common misconception. (Consider the dreaded essay question!) In reality, science and the humanities need each other. We are one: opposite sides of the same shiny coin of human existence. One cannot exist successfully without the other. While science is concrete knowledge, humanities are ethereal wisdom. There is no doubt about the importance of science to our civilization, but science run rampant will be the end of humanity. Science, we are your conscience. We are a beacon pointing the way for you to benefit man. We are the caring parent standing in the background with a watchful eye while science learns and explores. We are here; no glory, no fame, no fortune. We are here, self-sacrificing and diligent. Studying humanity is a noble calling. We are on guard against mechanized hopelessness as we mine for truth and meaning. As a beacon must, we will continue to shine on.

Paul Fulkerson and Bob Gidcumb, editors

Dr. Kietzman’s ENG 241 class