Finding Duende in Manchester – My visit pt. 3

In 1933, Spanish poet and dramatist Federico García Lorca gave a lecture entitled “Play and Theory of the Duende.” The goal of this speech, he said, was to “try to [give a] simple lesson in the hidden, aching spirit of Spain.” What followed were words tinged by ancient mystique and gypsy culture as Lorca described the artistic inspiration of the duende.

The duende’s arrival always means a radical change in forms. It brings to old planes unknown feelings of freshness, with the quality of something newly created, like a miracle, and it produces an almost religious enthusiasm.

Challenging, colorful views such as these, though, would mean death for Lorca. Three years later, civil war broke out in Spain. The poet was soon imprisoned by nationalist forces led by Francisco Franco, and on August 18, 1936, he was taken to a courtyard outside of Granada. There, along with a teacher and two anarchists, he was executed by firing squad at the age of 38.

–

So what is duende? It’s a word that does not translate well into English. The closest approximation would probably be catharsis – a sort of physical, indescribable reaction to a work of art. In the video below, celebrated flamenco singer Enrique Morente describes duende as the mysterious transmission found in art. This performance is a good introduction to the term – the simple rhythms and powerful voices seem to resonate with the old Andalusian bath.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hikNqOfvmos[/youtube]

My adviser, Eva, first explained the term to me in connection with Lorca and Morente, two artists she admires greatly. She went on to explain that she hopes to bring the concept of duende to the sciences as well. This may, at first, seem like an abstract concept, but scientists of radical and daring work have described a sort of duende-like response to their discoveries in the past. Albert Einstein himself, having had his general theory of relativity confirmed through the orbit of mercury, recalled being “beside [himself] with excitement” – he even experienced heart palpitations.

Later, he would tell his friend, he felt sure that something inside him had actually snapped.

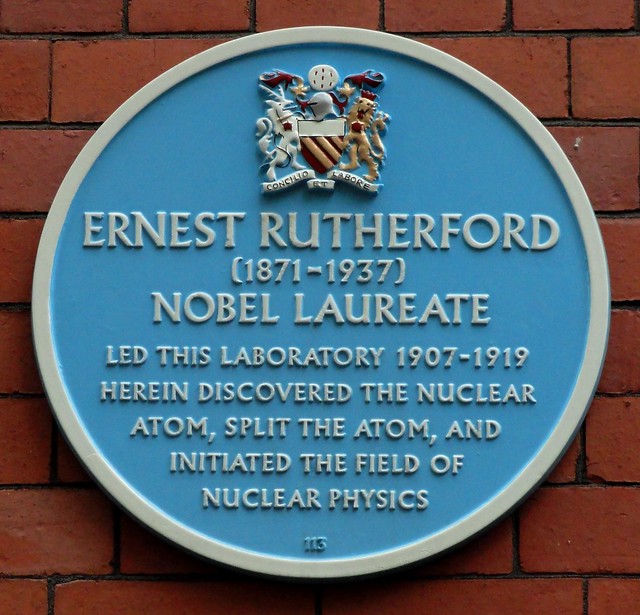

Manchester, in fact, has produced many scientific revelations. Across the street from my research office is the Rutherford Building, named after physicist Ernest Rutherford, who worked in the building’s laboratories. In 1911, he proved the existence of the atomic nucleus, and just six years later he was the first to “split the atom” through the artificial disintegration of nitrogen atoms. Rutherford described his discovery of the nucleus as “the most incredible event that has ever happened to [him] in [his] life.” Today, a plaque commemorates the man’s discoveries.

Rutherford’s Mancunian contribution to atomic structure was outdone only by Niels Bohr, a theoretical physicist who also worked in Manchester. In 1913, he extended quantum theory to atomic structure, effectively replacing Rutherford’s classical model with one that included the now-familiar orbitals. Remembering this discovery, Bohr explained his motivation as the need for a rebellious approach:

. . . that was the point about the Rutherford atom, that we had something from which we could not proceed at all in any other way than radical change. And that was the reason then that [I] took it up so seriously.

While the contributions of scientists such as Einstein, Rutherford, and Bohr may have been unique, they were all driven by a need for radical change. For figures such as Einstein (or, in a more understated sense, Rutherford), this change, when realized, produced a great physical reaction – almost a transformation. This feeling is not unlike that of duende described by Lorca; Bohr himself, having introduced quantum mechanics to what was a classical approach to the atom, worked to “[bring] to old planes unknown feelings of freshness” as duende did for Lorca. He would further this notion of the “unknown” by claiming that physics is at all times ambiguous and imperfect – it is only able to describe what humans can say about nature, not what nature truly is.

The powerful change brought upon by science or art, though, is not always positive. Lorca said of duende that “he rejects all the sweet geometry we have learned, that he smashes styles, that he leans on human pain with no consolation and makes Goya . . . work with his fists and knees in horrible bitumens.” For Goya, the artist mentioned, the rejection of traditional styles came in the form of madness and isolation. Working alone, he produced his “Black Paintings“, uncommissioned works he intended to never leave his home.

“Two Old Men Eating Soup”, an example of Goya’s “Black Paintings”

While Goya’s paintings may have taken a dark turn, Rutherford’s contributions would lead to actual deaths. The splitting of the atom initiated the creation of the atomic bomb that would kill thousands in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

–

In my own trip to the Manchester Art Gallery, though, I found the feeling of duende through the work of British artist Frank Auerbach. His works challenge conventions of portraits; working with drawings he has made, he obscures the details of his subjects with mountains of oil paint.

Frank Auerbach’s “Head of E.O.W.”

Works like Auerbach’s offer a unique new take on traditions such as the portrait, but it’s difficult to avoid being taken aback by the change. The figure in “Head of E.O.W.” looks almost skeletal or corpse-like in a pallid yellow. Many of the museum’s patrons, I noticed, seemed put off by the works. They moved quickly from Auerbach’s exhibit to a Victorian wing filled with the youthful glow of cherubs.

For Lorca, though, revolutionary change meant the acceptance of death. “Everywhere else, death is an end”, he said. “Death comes, and they draw the curtains. Not in Spain. In Spain they open them.”

While the effects and outcomes of radical change may be unknown and even foreboding at times, art like that of Auerbach’s, I feel, is a way for us to open the curtains.