On April 5, 2023, dozens of attendees converged on a lecture hall in the White building on University of Michigan-Flint’s campus for a presentation on how a focus on human-centered design can help us to have more equitable access to government and community resources. Researchers and designers, Kristen Uroda and Maki Nakagawa from Civilla were invited by the Urban Institute for Racial, Economic, & Environmental Justice (UIREEJ) to speak about human-centered design on their mission and what Civilla has accomplished so far.

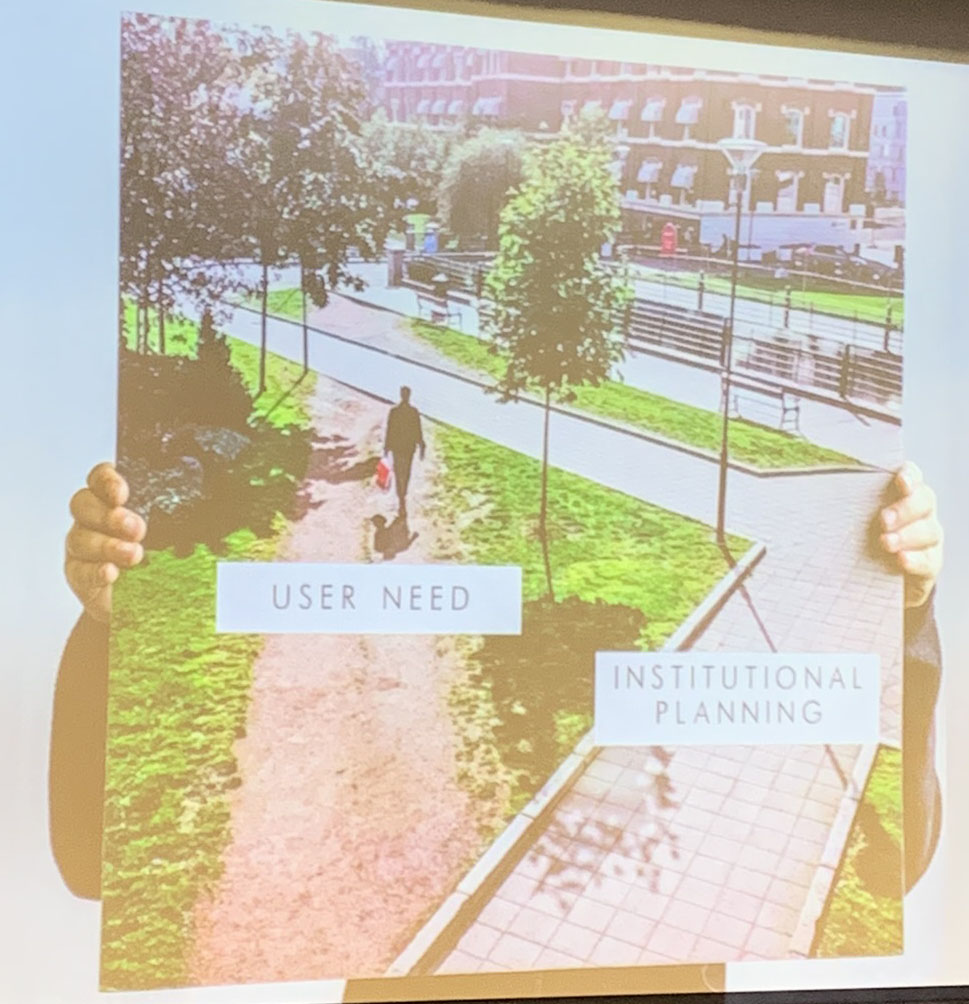

After a brief introduction from Jan Furman, executive director of UIREEJ, the Civilla presenters made a powerful demonstration of why their work is so impactful. They stated the vision of Civilla as “together, we believe the best and fastest way to scale positive social change is through public-serving institutions. But we can only do that well if we put people first.”

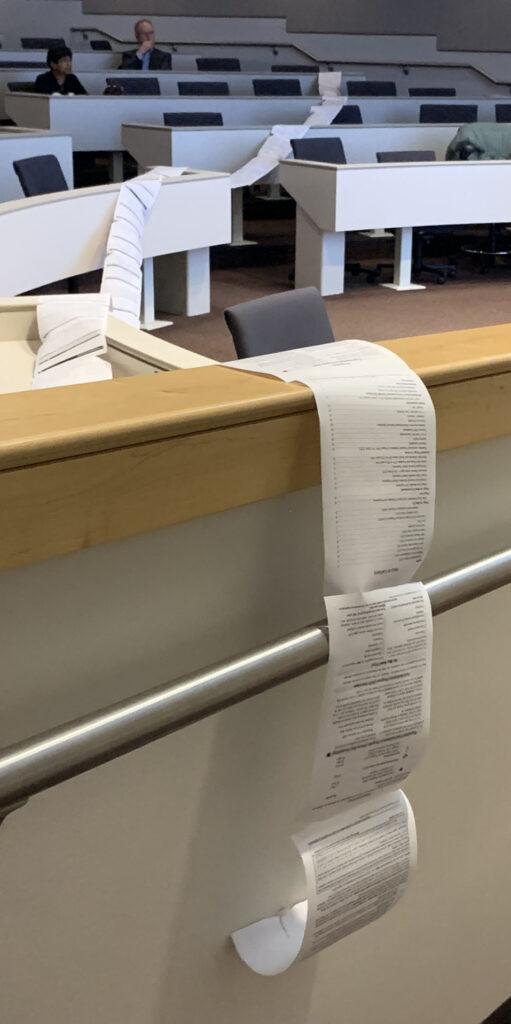

Nakagawa held up a large roll of paper, explaining that it was the inspiration that spurred one of the co-founders to get involved and start the company. Nakagawa and Toko Oshio, the REEJ faculty research cluster lead who initially invited Civilla to present at UM-Flint, began to unravel the paper scroll as he explained that it was Michigan Department of Health and Human Services form 1171, the form that individuals and families need to fill out to apply for assistance. The form was around 50 pages and 18,000 words long.

Nakagawa and Uroda explained that by helping the Michigan DHHS office to create and use processes to design the application process to consider the needs and perspectives of the clients served as well as the caseworkers and other front-line staff, they were able to reduce the size of the application by around 80%. Not only did it reduce the burden on those applying for relief; it also saved a measurable amount of caseworker time.

Uroda shared feedback from Michigan residents and caseworkers who experienced the process improvement that Civilla implemented. One resident said, “I felt like a number [with the old system] rather than a human with a complex story to tell. I was dropped into a system with no sense for where I was, where I was going, and the clear steps I needed to take to succeed.” Another said, “after filling out the new application, I feel like I can breathe again. The old application would have taken me a whole day. This one was more understandable and less stressful – it asks you the questions but with respect” (emphasis mine).

In addition to feedback from the residents themselves, Uroda also explained that the caseworkers really appreciated the process. They were able to focus more on their casework rather than data entry, they felt as if they were servicing the people rather than the systems themselves, and they were able to get through a larger volume of work in a shorter period of time. One DHHS Caseworker said, “you have to remind yourself everyday: this is an actual family. I am not just entering numbers. These are people that need our help.”

They explained that, in addition to empowering end users of the programs and processes, Civilla also meticulously instituted robust systems to ensure human-centered design remained central to the revision processes so they can deliver impact at scale through the long-term. Another caseworker said, “I have been involved with many initiatives within the state of Michigan over the years. I haven’t ever experienced the way this initiative is being communicated. You didn’t just tell us – you involved us.”

Nakagawa stepped back up to tell how Civilla helped do the same thing for Michigan’s Child Welfare systems. These systems are essential for helping to mitigate harm from abuse and neglect of children through such avenues as temporary placement. They were, however, plagued by “an unmanageable backlog of defects, incidents, and data fixes that [were] likely to persist indefinitely, inhibit effective casework, contribute to data entry errors, negatively affect outcomes for children and families, and impact MDHHS’s ability to collect and report accurate and timely data.”

“You have to remind yourself everyday: this is an actual family. I am not just entering numbers. These are people that need our help.”

Michigan DHHS Caseworker

Have you noticed in the past couple of years that you now receive a notice to renew your vehicle registration by mail? Or that the lines at the Secretary of State are quite a bit better? These changes, too, are a result of Civilla’s human-centered design approach.

“I’m really grateful that the Office of Research and Economic Development was willing to fund this presentation today,” said Oshio. Furman’s remarks speak to why: “It’s really important that we think about ways that we can embrace both compassion and efficiency in our institutions. My hope is that new connections can be made from this presentation today.”