Daba Coura Mbow

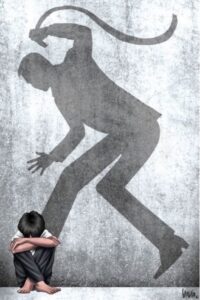

Children who witness aggressive behavior at home, from parents, are more likely to be aggressive in social situations later in life.

Some parents use physical punishment when kids misbehave, while others take away privileges. But do we know the consequences on children as they grow up? In 2016 the World Health Organization identified “protecting children from violence and adverse experiences that increase the risk of poor socioemotional development” as a global public health priority. Julie Ma, associate professor of social work, has centered her research on parenting, most recently, by looking at a global sample of families from over 60 countries, using comparable data, and strong statistical controls.

Ever since completing a bachelor’s degree in humanities, Julie Ma has taken an interest in children’s outcomes. Her original curiosity emerged from living in Germany and South Korea growing up. Living in very different societies, professor Ma saw as a young person how, where a child lives, really shapes how their parents interact with their children. She learned that physical punishment was a common practice used by many parents around the world, especially in South Korea where saw and experienced it. But while living in Germany, to her surprise, she learned that in some countries in Europe, physical punishment was banned. Eventually, these life experiences led her to research the research topic of how the environment shapes people’s attitudes, beliefs, and parenting practices. This became the basis for her Master’s and Ph.D. in Social Work.

More recently, Ma and her co-investigators are performing a comparative analysis with UN data. In one recent paper, they perform a Bayesian multilevel analysis on a hypothesis that kids who experience any type of violence at home, even as punishment, are more likely to become aggressive in their social interaction with friends, siblings, or pets. The underlying idea is that early exposure reinforces violence as a norm for behavior correction. They used data from over 200,000 families and analyzed associations of physical punishment and nonphysical discipline (i.e., taking away privileges and verbal reasoning to discourage misbehavior) with three different measures of the children’s socioemotional functioning: getting along well with other children, aggression, and becoming distracted.

Violence against children is really common, in a study of nine countries, over 50% of children had experienced slapping, hitting, or spanking by an adult family member within the past month (Lansford et al., 2010). In another study, 43% of children in Lower Middle-Income countries (LMICs) had been spanked in the previous month, and across 59 of the 62 LMICs in the study, spanking was negatively associated with 3- and 4-year-olds’ socioemotional functioning. Whether it is legal or not to hit children in some countries, we should understand the socioemotional consequence that physical punishment can have on children. This was the original insight Dr. Ma gathered from her own cross-cultural childhood. Julie Ma was able to see how different cultures have different norms of discipline for children, and that the family environment is a critical context of early childhood development (Irwin et al., 2007). Increasingly the research shows that exposure to violence, including parental physical punishment, is associated with poorer child socioemotional functioning (Britto et al., 2017; Herrenkohl et al., 2016)., In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), nearly half of the children are at risk of not meeting their developmental potential, in part due to adverse environments.

Globally, Dr. Ma shows, parents who are more educated and earn higher incomes are less likely to use physical correction. The stress of surviving for many low-income families often impacts how parents conceive of their child’s well-being and the capacity for parental patience. So parents who experience more stress, often turn to violence and substance abuse. These negative environmental factors t, which can include parents hitting children, have a very detrimental impact on social-emotional development. By contrast, children in high-income families have more social support and can offset the negative environmental factors, even the effects of physical punishment.

With all the variations in the culture around the world, the research indicates that eliminating physical punishment would benefit children across the globe. This finding aligns with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. It’s still very important for parents to set boundaries and use clear communication to let kids know what the expectations are. But, as Dr. Ma argues, more attention needs to be focused on nonphysical forms of discipline across the globe.