UM-Flint’s Department of Biology professor Dr. Heather Dawson recently conducted research with students on the Great Lakes Sea Lamprey. This research has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management.

UM-Flint’s Department of Biology professor Dr. Heather Dawson recently conducted research with students on the Great Lakes Sea Lamprey. This research has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management.

When asked about the value she finds in working with student researchers, Dr. Dawson said, “I have never conducted a research project that didn’t include students. It really is a win for both parties. Students gain experience and get to find out what research is all about. The research can also help guide the students regarding the direction they go after graduation. Faculty get great research assistants who help faculty to get much more research done than they could do by themselves. Faculty also get a chance to mentor future leaders in their field. I have worked with students on multiple research projects. Students can get involved on a volunteer basis, through the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program, or get class credit while conducting research. Conducting research with a faculty member also provides students with a reference (someone to write them a letter of recommendation) they will need to enter the work force or continue with further schooling.”

Dr. Dawson then explained the research she and her students conducted:

My research focuses on researching ways to improve the management of Great Lakes sea lamprey in an effort to protect native Great Lakes fish populations. Sea lamprey are non-native fish who invaded the Great Lakes in the 1930s, and have had devastating negative effects on native fish populations since that time. Sea lamprey are parasitic fish which attach themselves to large-bodied fish and suck out their blood and body fluids. Their main prey are native lake trout, whose populations collapsed soon after the invasion of sea lamprey in the Great Lakes. Sea lamprey have an interesting life cycle that starts with eggs laid in Great Lakes tributaries that hatch into larvae which burrow into stream beds. They spend approximately 3-7 years in the larval stage, and are harmless filter-feeders until they gain enough fat reverses to go through the process of metamorphosis. During metamorphosis they get eyes and teeth and head out to the Lakes where they spend their parasitic life stage feeding on large-bodied fish. They spend approximately 12-20 months in the parasitic stage, after which they head into Great Lakes streams in the spring and mature into adulthood. They quickly become sexually mature in streams where they spawn and die.

My research focuses on researching ways to improve the management of Great Lakes sea lamprey in an effort to protect native Great Lakes fish populations. Sea lamprey are non-native fish who invaded the Great Lakes in the 1930s, and have had devastating negative effects on native fish populations since that time. Sea lamprey are parasitic fish which attach themselves to large-bodied fish and suck out their blood and body fluids. Their main prey are native lake trout, whose populations collapsed soon after the invasion of sea lamprey in the Great Lakes. Sea lamprey have an interesting life cycle that starts with eggs laid in Great Lakes tributaries that hatch into larvae which burrow into stream beds. They spend approximately 3-7 years in the larval stage, and are harmless filter-feeders until they gain enough fat reverses to go through the process of metamorphosis. During metamorphosis they get eyes and teeth and head out to the Lakes where they spend their parasitic life stage feeding on large-bodied fish. They spend approximately 12-20 months in the parasitic stage, after which they head into Great Lakes streams in the spring and mature into adulthood. They quickly become sexually mature in streams where they spawn and die.

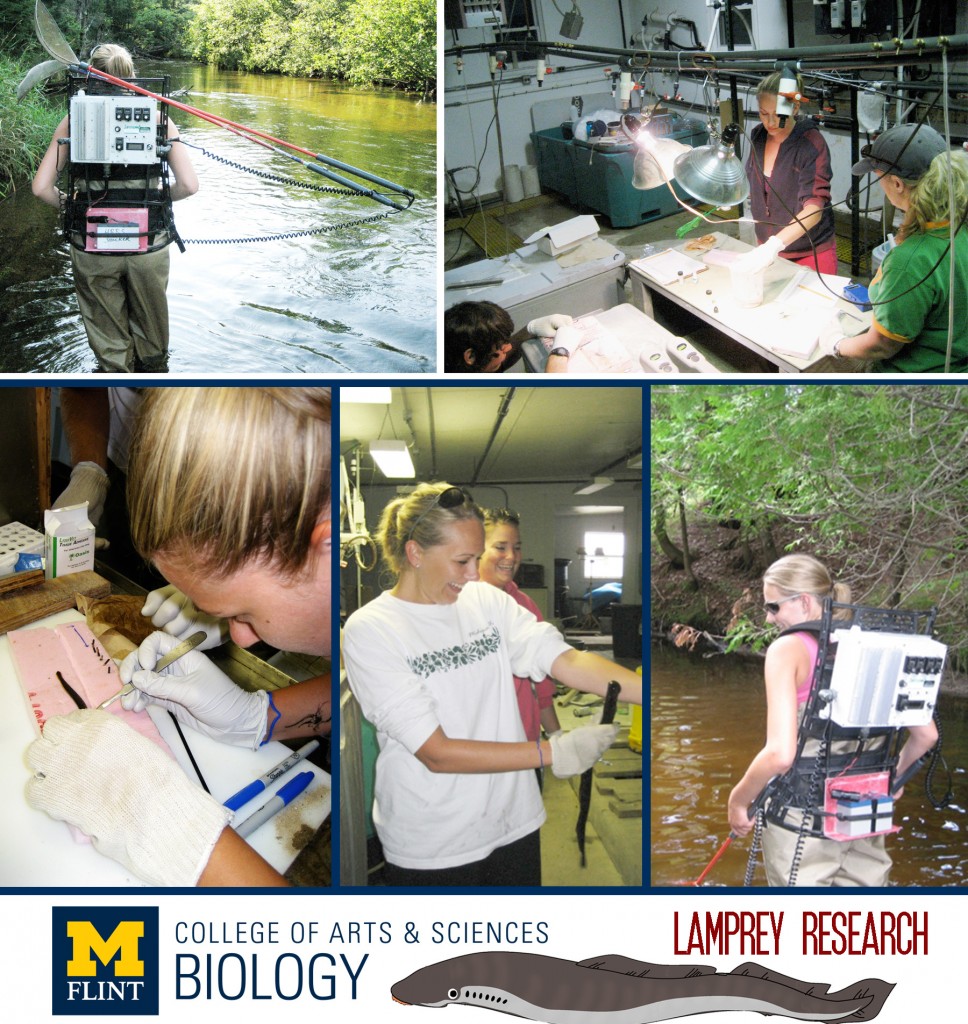

Danielle Potts was interested in studying animal behavior as part of her Master’s thesis at UM-Flint, so we discussed working together to study larval sea lamprey behavior. We wished to determine whether larval sea lamprey, who burrow into stream beds, change their habitat preferences and move downstream as they grow. An undergraduate at UM-Flint, Alex Maguffee, also joined us in conducting some of this research. Streams are ranked for chemical treatment where a lampricide is applied based on the number of large larvae that are projected to be killed per dollar spent. Larval populations are assessed by sea lamprey control agents on a regular basis to inform the ranking of streams for treatment. Sea lamprey control agents electrofish the preferred habitat of larval sea lamprey to catch sea lamprey at points along the streams so they can estimate the entire stream abundance of larval sea lamprey. Danielle and I wished to determine whether large larval sea lamprey also spend time in acceptable, but not preferred, habitat and whether they move downstream as they grow. If some large larvae do spend time in acceptable habitat, then sea lamprey control agents will not collect them, as they are only assessing preferred habitat, which could lead to underestimating populations of large larvae. If large larvae move downstream as they grow, then sea lamprey control agents may need to assess populations further downstream to get an accurate estimate of large larvae.

Danielle Potts was interested in studying animal behavior as part of her Master’s thesis at UM-Flint, so we discussed working together to study larval sea lamprey behavior. We wished to determine whether larval sea lamprey, who burrow into stream beds, change their habitat preferences and move downstream as they grow. An undergraduate at UM-Flint, Alex Maguffee, also joined us in conducting some of this research. Streams are ranked for chemical treatment where a lampricide is applied based on the number of large larvae that are projected to be killed per dollar spent. Larval populations are assessed by sea lamprey control agents on a regular basis to inform the ranking of streams for treatment. Sea lamprey control agents electrofish the preferred habitat of larval sea lamprey to catch sea lamprey at points along the streams so they can estimate the entire stream abundance of larval sea lamprey. Danielle and I wished to determine whether large larval sea lamprey also spend time in acceptable, but not preferred, habitat and whether they move downstream as they grow. If some large larvae do spend time in acceptable habitat, then sea lamprey control agents will not collect them, as they are only assessing preferred habitat, which could lead to underestimating populations of large larvae. If large larvae move downstream as they grow, then sea lamprey control agents may need to assess populations further downstream to get an accurate estimate of large larvae.

We investigated the feasibility of tracking individual sea lamprey to study their behavior by using passive integrated transponder (PIT) technology to detect sea lamprey larvae in their burrows underneath the stream bed. PIT tags are small tags that can be implanted internally into an animal and has a unique identification number that can be read using an antenna. We found that the smallest tags available (8 mm in length) are still too large to be implanted into larval sea lamprey >100 mm in length without causing significant mortality. We also found that the burrowing ability of tagged larval sea lamprey was significantly worse than untagged larval sea lamprey. Tagged larval sea lamprey took much longer to burrow, which likely increases their susceptibility to predation. We did find that large larval sea lamprey have a tendency to move downstream as they grow. However, to really study larval sea lamprey in streams, smaller tags are needed to track individual larval sea lamprey to ensure that the majority can survive tag implantation and that their natural behavior is not affected.

Dr. Heather Dawson can be reached by email: hdawson@umflint.edu.

For more information on the UM-Flint Biology Department, please visit their website.

To view current student research opportunities, please visit the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP) page.