No one was making me go to church when I returned except, perhaps, John Milton, the English poet, revolutionary, and blind composer of Paradise Lost. I had been an undergrad at Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts, and was nearing the end of a Ph.D. at Boston College—another Jesuit school to round off my Catholic higher education. The Jesuits at both colleges said Mass many different times throughout the day, and I attended sporadically, bingeing but not feeling the obligation to get up on Sunday morning or to adjust my schedule around Mass on Holy Days of Obligation. I guess you could say that I went through a mild rebellion—a phase of tasting my own freedom. I would even spend the year after completing my Ph.D. teaching in Ankara, Turkey. The parish priest at Our Lady of the Annunciation in Glens Falls, New York urged my mother to dissuade me from this plan since “she won’t be able to attend Mass.” I ignored the warning, went anyway, and found mosques wonderfully meditative places for private prayer. I was not on the run from my faith. In fact, traipsing around the world confirmed what I’d decided with intellectual conviction during my Ph.D. work that autonomy is an illusion and freedom is a matter of consciously and conscientiously choosing or creating our own constraints—those orders to which we bind ourselves. At a time when I was still in grief over my father’s death, I had unconsciously chosen a fitting subject for my dissertation—trauma in narrative: specifically, how female characters in Renaissance literature re-make themselves after world-shattering experiences of rape, war, famine, and political powerlessness. The solution, proffered by great and small authors alike, seemed to be articulation, complaint, the artful attempt to connect with others. In Milton’s retelling of the Genesis fall story, Adam and Eve re-connect as a couple because Eve voices a moving complaint in which she accepts her share of responsibility for a quarrel that culminated in separation, temptation, and finally breaking God’s single command. She admits to being a rib crooked, a fragment broken from a whole; and her vocal humility creates the conditions for the first true conversation between Adam and her.

I would walk all over Boston, meditating on stories like this one from Milton’s great epic. Living in Roslindale, at the time, I walked regularly from the edge of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum up to the top of a very high hill and into the basement of an old brick, totally uninspiring yet clearly serviceable, Catholic Church. The religion of my childhood was suddenly illuminated by the religious literature I’d been studying; and I knew once again, in a different key, that I was not free. I, too, was a fragment, broken from the whole host—a white sun-like orb—raised at the consecration as pure and perfect as I hopefully imagined my soul. What relief and release there was in realizing that, no matter what dunghill I cried from, something could come of what I cried. Religion—an ordered spiritual drama like the Mass—actually supported the major writing project I’d undertaken. I understood then that it was the absolutely essential supportive framework for creativity in general because it helped me believe in all that I’d not yet spoken. Committing to religion—like committing to love—is a way of freeing what waits within us so that what no one has dared to wish for may for once spring clear without my contriving.

I am more skeptical than Jan Worth-Nelson who, in a recent editorial in the East Village Magazine, praised secular society for the freedom it gives us to “quest for authenticity.” Like Jan, I teach at the University of Michigan-Flint; but, I was not a natural teacher. First, I was a rebel child, a school-phobic crazy who hid in the woods, thinking lessons an interminable waste of time and a distraction from what was real. My wild rebelliousness happened long before puberty, and I grew into a very inward girl—the kind of student who never spoke out in high school, college, not even graduate school. I learned to speak only when I had to teach. All terribly shy people will know the intense build up of an almost erotic energy when we so badly want to throw our words out into the current of life like a fly fisherman but tangle ourselves in the endless loops of anxious questioning: What if they think I’m stupid or awkward? What if the teacher doesn’t listen? What if I can’t remember my idea? And we don’t allow ourselves to ride the words, the thoughts, crafting the experience in mid-air. I felt very early in my life that school damages us because it ties articulation to self-image. It is, as I perceived from my childhood “forts” in the pinewoods, a place for fakers who are good at self-presentation. School, academia, secular society all reward schmoozers—those who, in one way or another, excel at self-presentation. Masking as self-actualization, self-presentation is the business of some writers and artists—even teachers. They care more about how they are being perceived than about the content of what they are saying or the students they are addressing. But I think the real job of writers and teachers is to free the secret inner voice within each person, but first we have to find ways of dropping our own self-presentational mask. This is not easy since almost all institutions reward slick talkers and self-promoters—all institutions but one … the true church.

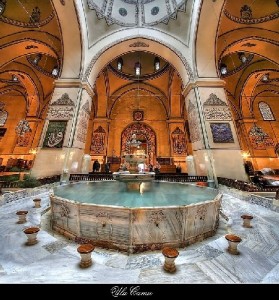

My mother was a lot like the mothers in Flannery O’Connor stories—sweet, well-meaning, concerned about neighborhood gossip, often platitudinous and sometimes bossy. Now that I am a mother, myself, I see that these traits are part of the role. But kneeling next to her in the pews at our small church, imitating the way she cupped her hands over her face when she prayed, having time to examine her spotted hands and sterling silver charm bracelet with a medallion engraved with the serenity prayer, hearing her sing off-key, I felt that she, like me, was just human. I sensed that she might have an inner life and wondered what she believed and what she prayed for. Richard Rodriguez, a Hispanic American makes an argument in his controversial autobiography, The Hunger of Memory, for monolingual education as necessity for successful assimilation. But this is his argument. All the poetry of his beautiful memoir is in his nostalgia for lost languages and secret voices, and Rodriguez longs for the Latin Mass as much as he longs for the revoked birthright of his mother tongue. He is grateful to the Catholic Church—the liturgical Church—for treating his laboring parents as thinkers—persons aware of the experience of their lives, and he writes a heartfelt paean to the “holy tongue” of Latin that enabled thinking because it encouraged an “aimless drift inward.” When I first read and taught Rodriguez’ book in freshman English at Boston College, I knew from experience that he was right about the value of a “holy language.” I, too, had sought the peace of foreign churches and traditions where I felt the vibrations of my own soul: in the dark around a wood stove in the women’s room of the Greek Orthodox monastery in Newton, Massachusetts; participating in the Latin liturgy at a Catholic church in London; barely understanding the thick brogue of the priest in an Irish parish in North London where the congregation reconvened in the pub after Mass, the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Semey, Kazakhstan where my daughter and I wandered from icon to icon, lighting candles and praying in whispers, lifted on the waves of human voices chanting adoration. I have prayed on carpets in mosques to the sound of interior fountains and even beat a tambourine to the rhythm of an ecstatic preacher at a revival on Asylum Street in Flint—“If we can’t praise Him here, ain’t no need to go up there. Heaven is a prepared place, and right down here is where we prepare.” AMEN! Each face, beaming more brightly than the red velvet carpet inside the “Hands of Love, City of Refuge Church,” was, in my estimation, ready to enter heaven if the rose-colored clouds of evening opened.

When we pray the Mass in English, we may lose poetry, music, rhythm, time to say the rosary and whisper our own prayers; but, church is still better than school. Even my eleven year old daughter thinks so. Education over-trains our sense-making faculties. As soon as we’re given anything to read, we focus on “getting it” and, in the process, fail to attend to the nerve of our own most intimate sensitivity. But the liturgy in any language has its own dramatic rhythm, its own cryptic symbols, its own lights and darks; and if we give ourselves to the hour-long drama, the rhythm will loosen our minds from sense-making tasks, engage our subconscious responses; and each congregant—involved in his or her own spiritual reality—will be set free to express needs and longings, sorrows and joys. I attend St. Michael’s Catholic Church in Flint. The visiting priests (most of whom are retired) all speak English, and yet, I still feel that I am one of a group of individuals who are together without masks. I can easily tell from body language when people are having trouble; it is written on their faces, the tears trickling from eyes, the bent shoulders, the oxygen tubes, the limps. Church is a place where we really are free to be human. When I am having a hard time physically, I think of John Paul II who insisted on functioning as the pastoral leader of the Church even through illness because he believed it was important to demonstrate that every human being had a valuable contribution to make. He was making a point about not having to be perfect, and it is one I consciously emulate on those days when insomnia leaves me feeling raw and unfit to appear before my students. “Focus on what you have to say … on what you feel passionately about,” a kind friend once said. I do.

I believe each human being has some kind of wild strength, and the mess we’ve made of the planet should be all the proof we need that we have been set down here to tend or destroy our garden. Supposedly living the American dream, we are not so different from the imperfect Israelites in prehistoric Canaan—a world of perpetual warfare, violent words, and political corruption. The central story in Judges is that of Samson, the strong man who, through aggression learns about his own strength (he can kill lions with his bare hands and slay thousands of Philistines with the jawbone of an ass) and who, through acting on his profound desire for Other women, is driven straight into the mystery of his own identity. Read his story in Judges 13-16, and you will see that Samson is much more than a superhero but a wise fool and poser of identity riddles who intuits that men must come to the limits of their strength to taste sweet waters of God’s mercy from a desert wadi. I am reminded of Yeats, the magnificent poet of age declining into decrepitude, who, when looking back over the efforts of a lifetime from the end of his own strength, wrote in “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,”

I am content to follow to its source

Every event in action or in thought;

Measure the lot; forgive myself the lot!

When such as I cast out remorse

So great a sweetness flows into the breast

We must laugh and we must sing,

We are blest by everything,

Everything we look upon is blest.

Doesn’t the warm sun feel so awfully good on cool days in late summer, especially after a brave swim in a cold lake? We did nothing to make the sun appear, but it does. It is like that with Church and with God; the feeling of being blessed despite our flaws teaches us that we can only be ourselves when we acknowledge that, whether we like it or not and despite the ebbing and flowing tides of our human relationships, we can (each one of us at any moment) experience the ecstasy of being passionately in love with One who seeks us quietly in a still, small voice that we can hear only if we turn down the volume of our presentational voices. “Hallowed be Thy name.”

Instead of going to church on Sundays, Jan Worth-Nelson remembers walking the streets and imbibing freedom. Walking can certainly be a form of prayer, especially in the more unpretentious and mixed up neighborhoods of Flint—like the East Village—where homeless men and women collide with students, professors, factory workers, alcoholics, and no one is made up or made over or trying to make an impression. Flannery O’Connor, defended herself when she was accused of writing too much about “freaks and poor people,” explaining that writers love the poor because “they live with less padding between them and the raw forces of life.” What I notice everyday from my own front porch is that those who live hand to mouth are often the people with a freewheeling energy, generous with pick-up lines, hugs, and all the time in the world to observe this stage-play world sidewalk-side in cheap plastic seats. The tiniest act of human kindness, a moment of shared humor in public, seem to set things right again as if any sign of human contact releases an unwanted tension.

But I think each of us needs friendship, special supportive friendship—not the casual kind, that encourages us to think, breathe, dream aloud—to unroll the pictures in our minds to the music of our spirits. We need an audience of one that gives us some approximation of what we had (if we were lucky) once upon a time, “Look, Mom! Watch this!” Fear squashes a voice, and, as anthropologist, Kirin Narayan, reminds us,”professional training narrows the color and range of possible tones. Too many outer demands brick up a flowing voice, forcing it so far underground you may forget its sounds.” How then is it possible to remain true to yourself as a writer while also attending to all the complications of a life involving other people’s expectations and demands? Get thee to church, take a walk, cultivate a friendship as if it were a garden bed for seeds of ideas. In any way that you can, turn inward and feel the current of longing for something. That is your self. Live in that current for a while and you speak from it to make the music more intense.

Thankfully, I found in middle age one friend with whom I’ve been reading the Bible from the first chapter of Genesis. Accustomed to hours of solitary study in preparation for teaching, I have been stunned by how much farther two people, working together, can go in the pursuit of meaning. Why is that? Perhaps this is why in all three monotheisms, there is a tradition of studying in pairs. For example, the foundation of all Sufi orders (Sufiism is the mystical sect of Islam) is the relationship between the teacher and disciple, cultivated through conversation and chanting or reading spiritual poems. This practice of composing and chanting poetry (nefes or “breath of spirit”), the feelings and devotion toward one’s particular teacher are endlessly evoked and elaborated. It seems fitting that the way to spiritual discovery and discernment be linked to its actualization not by man or woman working in isolation but as part of a pair. Even when I read the Bible alone in my room, I know that my friend is wrestling with the same stories wherever he is and perhaps is finding different things. My attunement to him heightens the feeling of encountering a vastly different world—in the biblical narratives, yes, but also that of my friend’s mind and his religious traditions. When we meet, the atmosphere is charged with hope, support, and attention. It is a pressurized and rarified atmosphere in which discoveries are more apt to occur. The shared bond of attention and mutual respect is a useful elixir in the creative process. Sometimes our meetings feel like coming face to face with a burning bush—frightening, confusing when we disagree, demanding, but most always illuminating. Coming to spiritual understanding through the human medium of conversation reminds me that, since my baptism, I have been in a covenantal relationship with YHWH. Covenant—human and divine—is another word for binding love that changes the world. Without an awareness of it, spiritual life becomes another playground for the solipsistic imagination—a woods for adult fort-building. I have learned from my friend’s Jewish tradition that the true expression of covenant love (hesed) is “doing before knowing.” This is not a childish. Neither is it an abnegation of intellectual freedom. Rather, it puts us in touch with the source of human strength which really is beyond us. “We will do and we will hear,” say the Israelites at the foot of Mount Sinai in the pledge to be forever engaged and attentive to God’s voice.

Here in mid-Michigan where there are no mountains and we are probably not going to hear God’s voice in clouds and thunder, we can seek places, relationships, and practices that relieve us of the burden of having to be presentable, where we can hear and speak in our secret voices, whispering intimate truths with a resonance we recognize as music, not of our making alone. Chekhov’s homelier metaphor may get closer to the way most of us feel about our voices: “There are big dogs and little dogs, but little dogs must not fret over the existence of the big ones. Everyone is obligated to howl in the voice that the Lord God has given him.”